Moss was put on the exterior of International Space Station—after 9 months, its growth stunned scientists

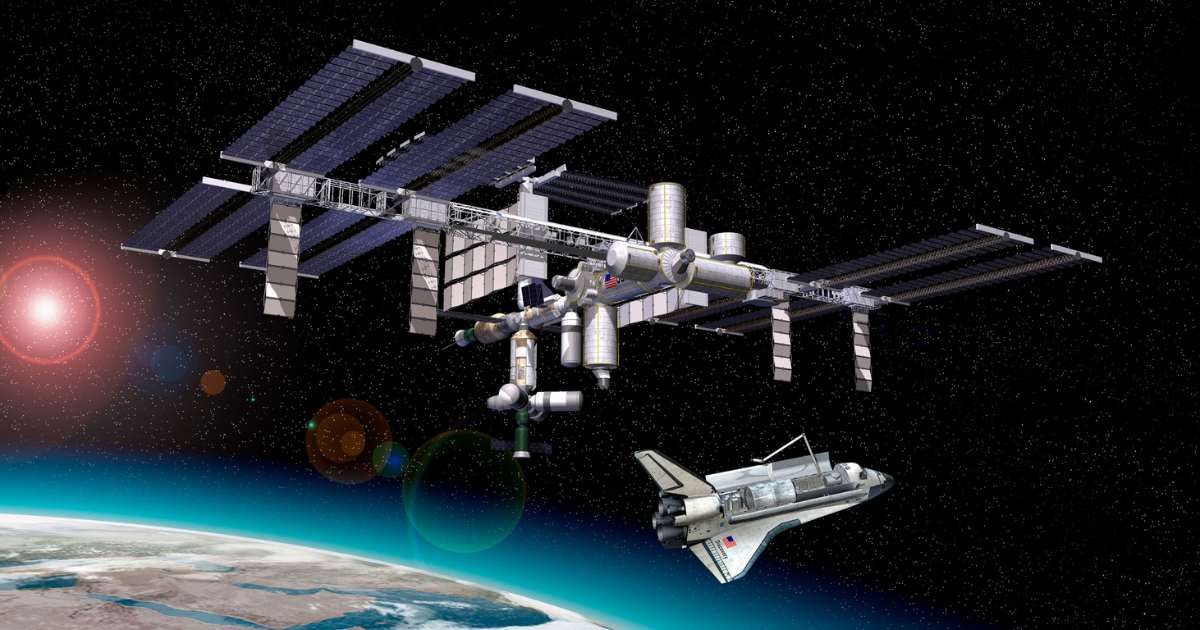

Whether it is the peaks of the Himalayas or volcanic lava fields, mosses are everywhere. However, it now appears that they can also survive in space. Researchers attached samples of the moss, Physcomitrium patens (P. Patens), to the exterior of the International Space Station, and their findings, published in iScience, state that they not only survived but “retained their vitality.”

Upon testing three cell types of P.Patens from different stages of its reproductive cycle under simulated space conditions, researchers found that sporophytes (cell structures encasing spores) showed the greatest resilience to high levels of UV radiation. Moreover, they were able to germinate even after being exposed to temperatures as high as 131 degrees Fahrenheit (for a month) and minus 320 degrees Fahrenheit (for a week).

Cut to March 2022, hundreds of sporophytes were sent to the ISS aboard the Cygnus NG-17 spacecraft. They were then placed on the exterior of the space station, where they survived for no less than nine months before they were brought back to Earth by a SpaceX cargo mission, according to NBC News. “Surprisingly, over 80% of the spores survived and many germinated normally,” the study’s lead author and professor of plant biology at Hokkaido University, Tomomichi Fujita, wrote in his email to Live Science. Granted, some samples suffered damage in space conditions. But even then, P.Patens showed much more promising results than other plant species that were tested under similar conditions.

The researchers said that sporophytes may have acted as a protective layer, enabling an 86% germination rate even in samples that had been fully exposed to UV radiation in space. “This protective role may have evolved early in land plant history to help mosses colonize terrestrial habitats," Fujita said. Based on this, Fujita and his team came up with a model that suggests that moss spores could survive in space for as long as 15 years. “If such spores can endure long-term exposure during interplanetary travel and then successfully revive upon rehydration and warming, they could one day contribute to establishing basic ecosystems beyond Earth,” he added.

That being said, Fujita noted that the study only focused on the chances of survival under space conditions. Whether the results will be the same when moss is put under various extraterrestrial conditions, including different gravitational and atmospheric conditions, is yet to be determined. Even though Dr Agata Zupanska of the SETI Institute, who was not part of the study, applauded its findings, she reminded that similar experiments had already been conducted outside the International Space Station. And even though the exterior of the space station has harsh conditions, it was not as challenging as the environments on the Moon or Mars.

“The value of space plants is realised only if they can actively grow and thrive away from Earth,” she said. “While spore resilience is important, it represents only an initial step toward the broader goals of growing plants in extraterrestrial environments.” For Fujita, this study was only the beginning. He hopes to conduct similar experiments on other species to achieve a better understanding of how these cells can hold their own in such extreme conditions.

More on Starlust

What happens after the International Space Station is gone?

Earth’s radio signals highlight regions where extraterrestrial life could find us