Half-century-old Apollo 17 moon sample uncovers new clues to the origin of a lunar landslide

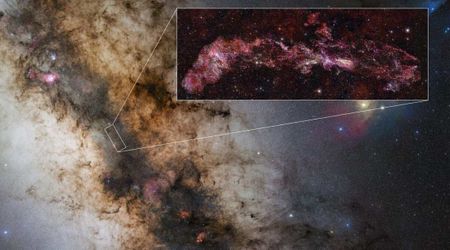

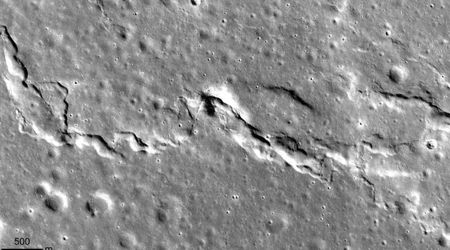

Fifty years after the last Apollo mission, a sealed lunar rock core is finally providing new insights into one of the Moon’s most peculiar features. A recent study of a sample from the Apollo 17 mission has uncovered new evidence about the Light Mantle, a prominent bright streak on the lunar surface. Scientists have long suspected this feature to be the remnant of a massive, ancient landslide, but its cause has remained a mystery, according to the Natural History Museum.

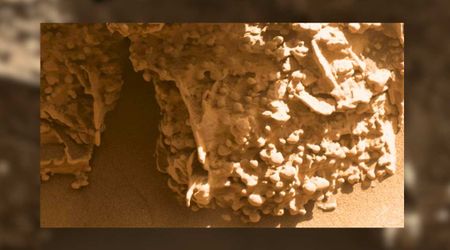

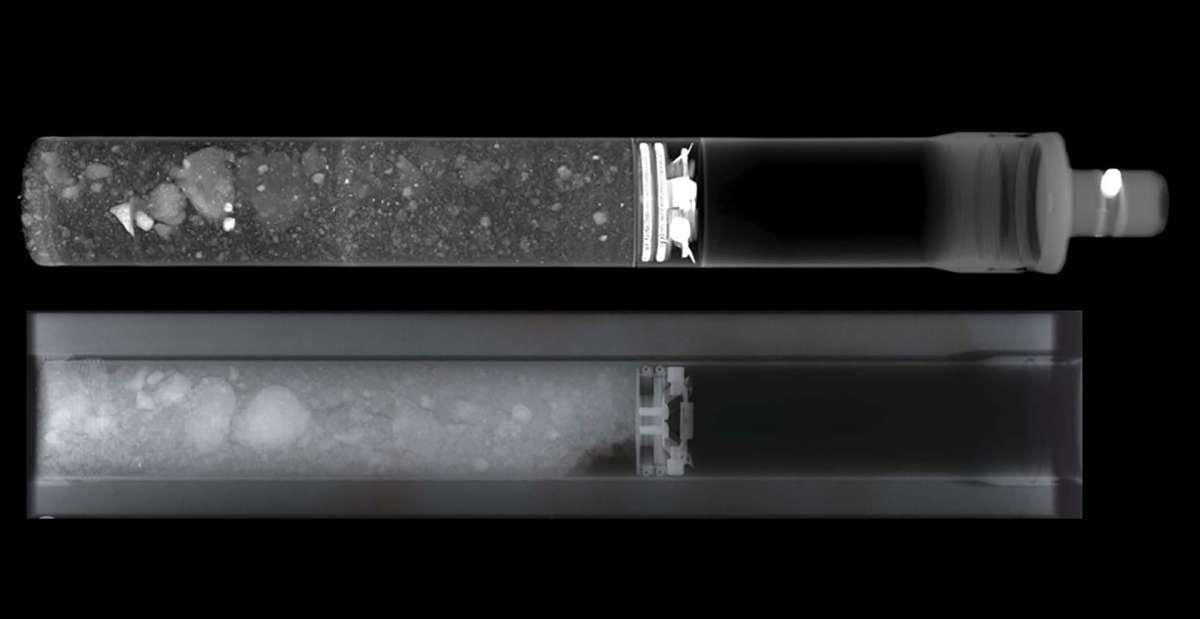

For half a century, the core sample was kept in a vacuum-sealed container to preserve it for future research. Now, armed with advanced technology unavailable during the Apollo era, scientists are getting a detailed look at the core’s contents. A team led by planetary geologist Dr. Giulia Magnarini used modern micro-CT scanning to analyze rock fragments, or clasts, within the sample. Their findings suggest that the landslide moved more like a fluid than a typical rockfall. The fine material coating the clasts appears to have come from the clasts themselves, indicating they broke apart during the descent and helped the massive debris flow over several miles.

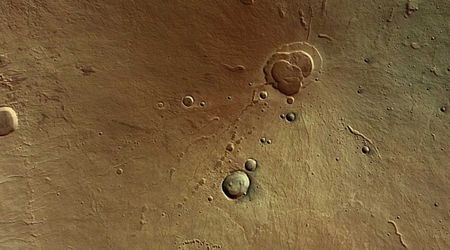

While the exact trigger for the landslide is still being investigated, one theory points to the asteroid impact that formed the Moon's vast Tycho crater. Debris from the impact could have traveled thousands of miles, striking the South Massif mountain and causing the landslide that created the Light Mantle. The research, published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, highlights the enduring scientific value of the Apollo samples. According to Dr. Magnarini, the study is also helping to inform the next generation of lunar missions, specifically the Artemis program. “This research is a way of continuing the legacy of the Apollo missions more than 50 years later, providing a bridge to the planned Artemis programme,” she explains.

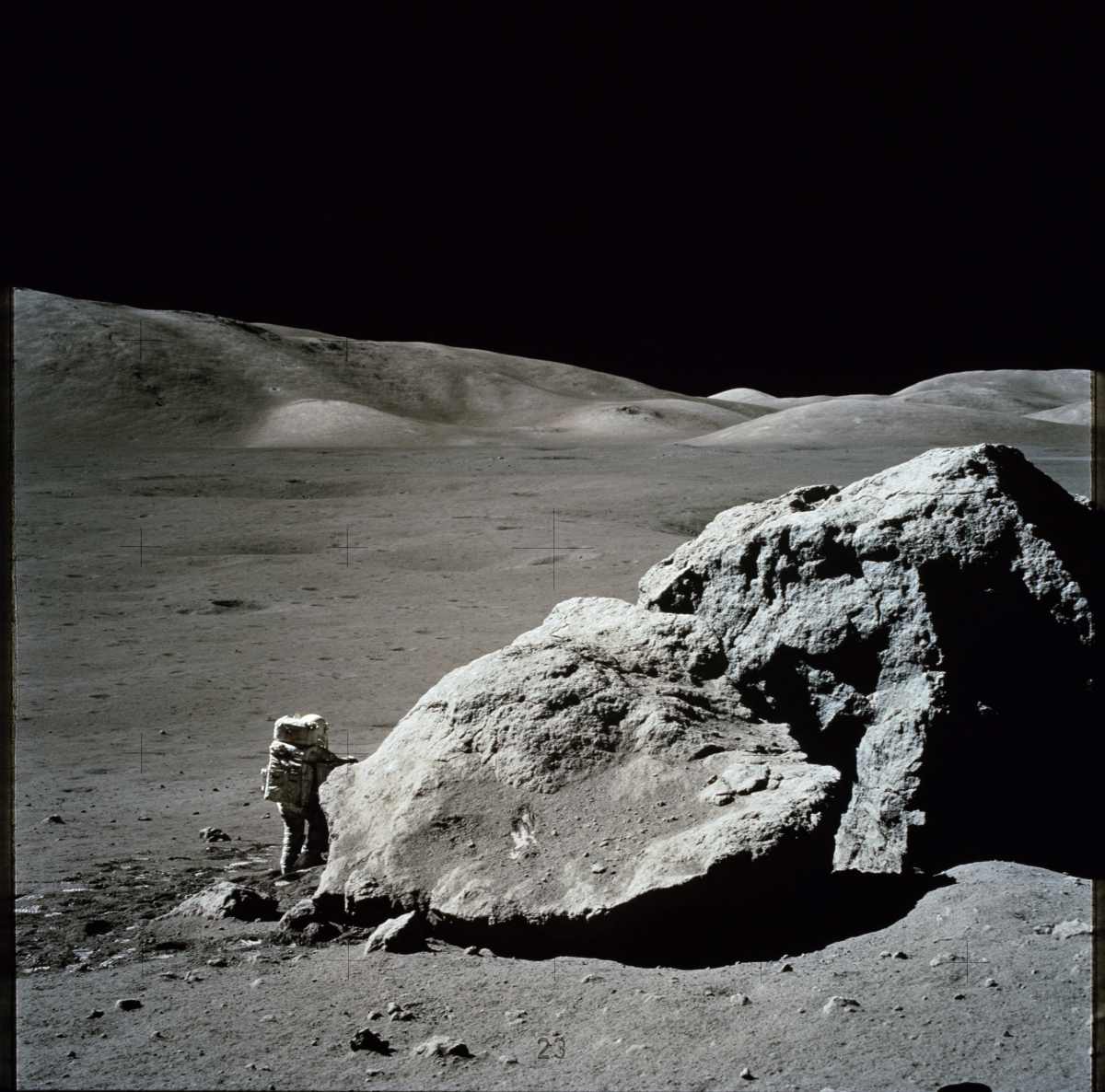

The Apollo 17 mission in 1972 was the first to include a trained scientist, geologist Harrison Schmitt, among its crew. Schmitt and fellow astronaut Eugene Cernan collected a record amount of lunar material, some of which was specifically set aside for future study with more advanced tools. This foresight is now paying off, as new findings from these historic samples continue to shape our understanding of the Moon and prepare us for a return to its surface.

The same historic Apollo 17 samples that are shedding light on the Light Mantle are also helping scientists determine the Moon's age with unprecedented precision. A separate study published in Geochemical Perspectives Letters has pushed back the Moon's estimated birth by an additional 40 million years.

Astronauts Eugene Cernan and Harrison Schmitt collected the dust and rock on December 11, 1972, and initial analyses had pegged the formation of the Moon's crust at 4.425 billion years old. However, a new analysis of the samples found incredibly old zircon crystals. These tiny crystals were dated to be 4.46 billion years old, making them the oldest known solid materials to form after the giant impact that created the Moon. “These crystals are the oldest known solids that formed after the giant impact. They serve as an anchor for the lunar chronology,” said senior study author Philipp Heck, a Robert A. Pritzker Curator for Meteoritics and Polar Studies at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago.