Giant mysterious equatorial spikes on Pluto may be made of methane ice

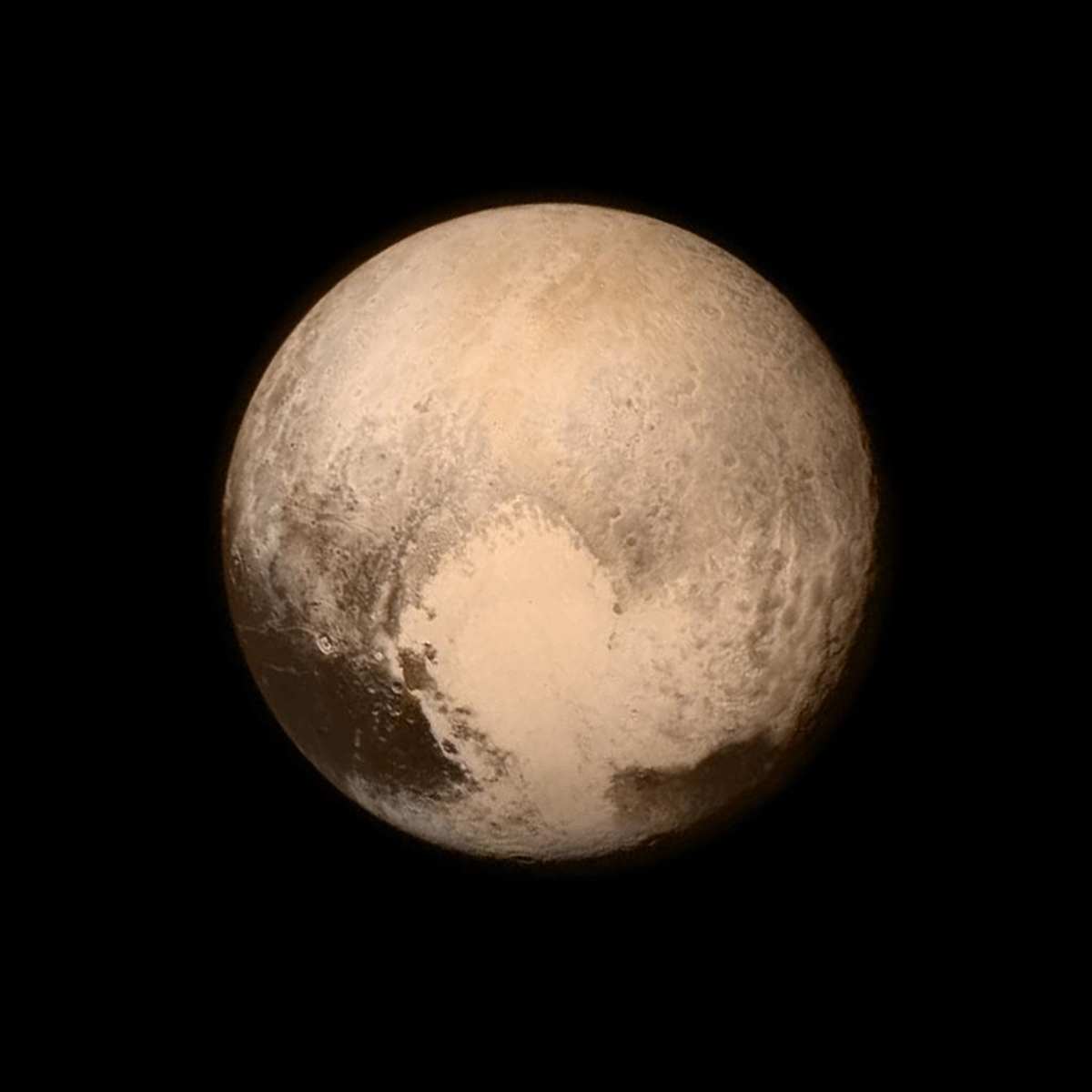

A new study revealed that towering spikes of methane ice may cover a significantly larger portion of Pluto's equatorial region than previously believed. The research, published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, suggests that these skyscraper-sized formations could encircle up to 60% of the dwarf planet, according to Live Science.

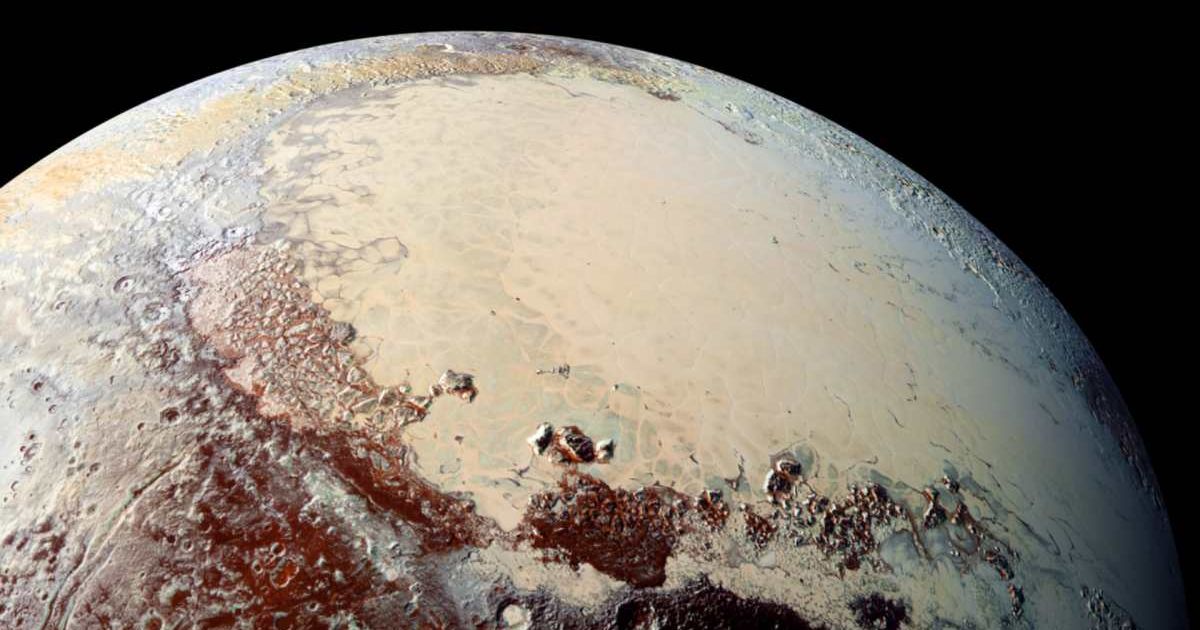

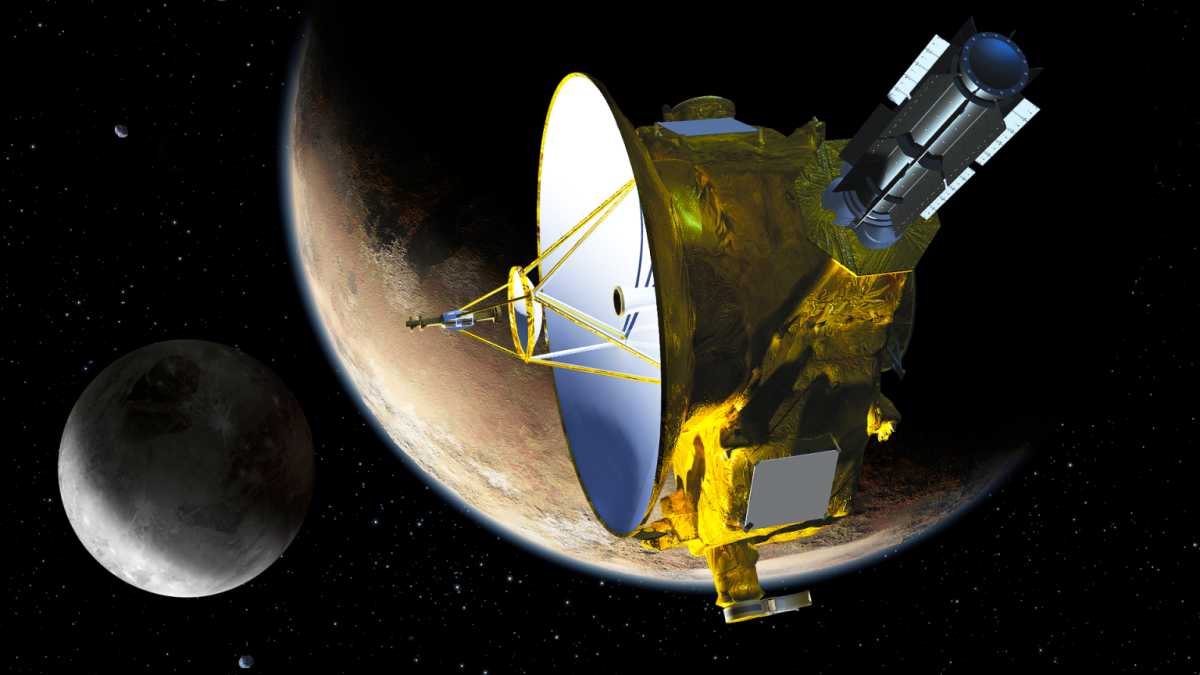

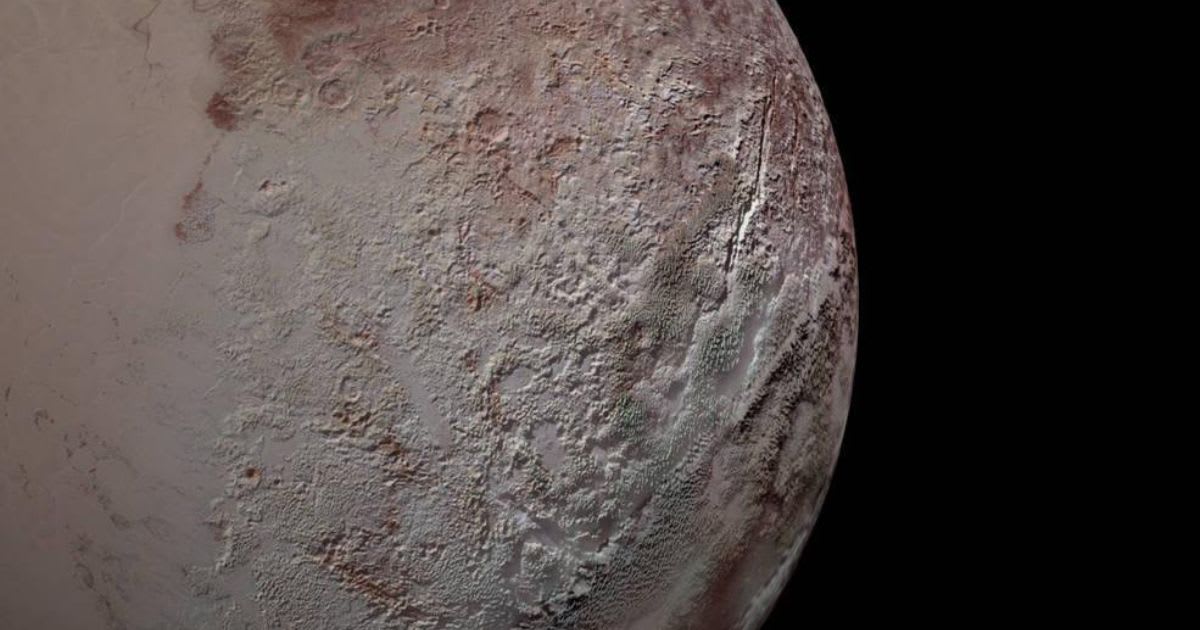

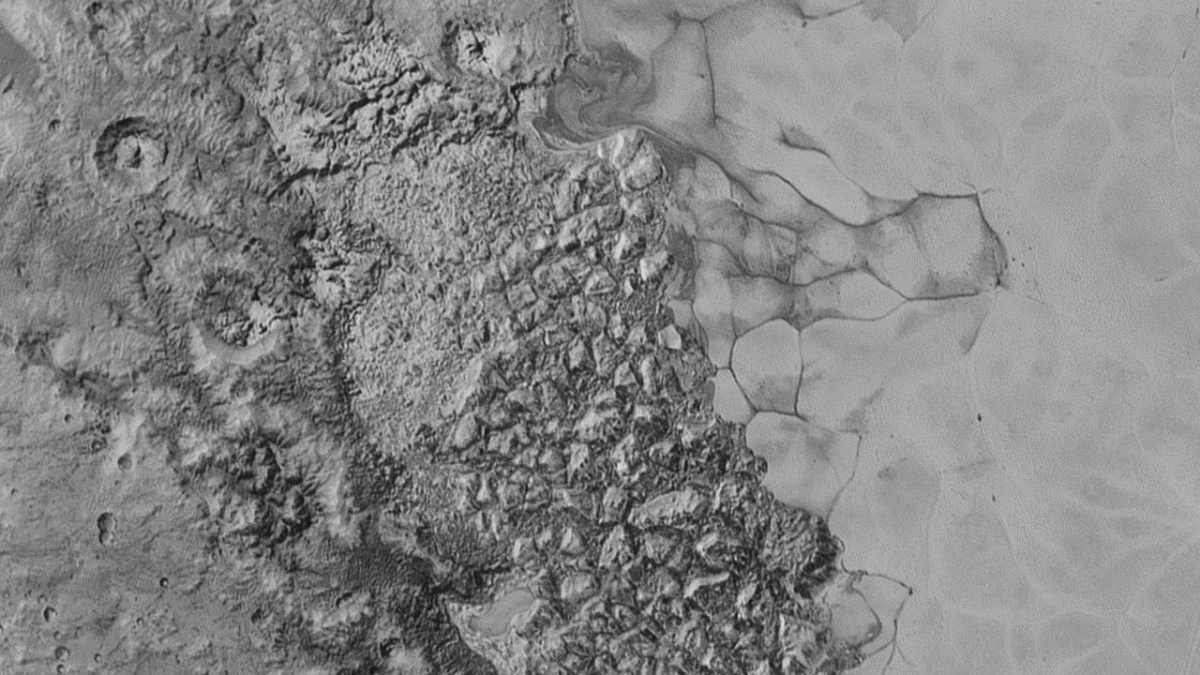

The findings are based on data collected during NASA's New Horizons spacecraft flyby in 2015. While the probe captured direct images of these "bladed terrain" formations in one area, researchers used indirect clues to infer their presence elsewhere. The spire, which stands roughly 1,000 feet tall, comparable to the Eiffel Tower, was initially spotted in the Tartarus Dorsa region, an area of high-altitude terrain near the dwarf planet's famous heart-shaped feature.

The study's authors, led by Ishan Mishra of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, analyzed how Pluto's surface reflected light from various angles. By studying surface brightness and its correlation with roughness, they discovered that other methane-rich areas of the planet were also exceptionally rough. This "darkening" effect, caused by shadows from surface irregularities, suggests that the bladed terrain extends into areas that were not directly photographed by New Horizons.

This new evidence points to a massive band of these icy spires spanning a majority of Pluto's circumference, five times the width of the continental United States. The formations appear to be concentrated in a specific latitudinal band where climatic conditions are ideal for their development. However, scientists say more research is needed to determine if the band is continuous or fragmented. "Until then, studies like ours offer the best indirect evidence using the available data," Mishra said. A future mission to the dwarf planet would be the most definitive way to confirm the bladed terrain's extension into Pluto's dark side.

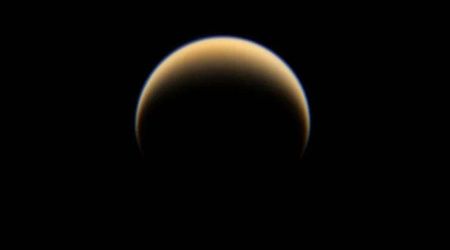

In a separate but equally intriguing planetary development, scientists have discovered that the icy shell of Titan, Saturn's largest moon, may contain a massive, six-mile-thick layer of methane ice. This unique discovery could have significant implications for the search for life beyond Earth. Titan is often compared to Earth because it's the only other body in our solar system with a dense atmosphere and liquid bodies on its surface, though its rivers and lakes are made of methane and ethane instead of water, as reported on Live Science.

This research, conducted by a team at the University of Hawaii at Mānoa, suggests that a thick layer of trapped methane gas beneath the surface ice could be warming the moon from within. This internal warmth may allow molecules from a suspected subsurface ocean to rise to the surface, where they could potentially be detected by future missions. This finding could make the search for biosignatures, or signs of life, on Titan more feasible. Additionally, the discovery may offer insights into the fight against climate change on Earth, as the trapping of methane in ice is a phenomenon relevant to our planet's environmental systems. The discovery of this potential methane layer has significant implications for astrobiology, as it could act as a crucial link between Titan's subsurface ocean and its surface.

"If life exists in Titan's ocean under the thick ice shell, any signs of life, biomarkers, would need to be transported up Titan's ice shell to where we could more easily access or view them with future missions," said Lauren Schurmeir, a planetary scientist at the University of Hawaii and the leader of the research team. She added, "This is more likely to occur if Titan’s ice shell is warm and connected."