Astronomers using JWST discover an ancient supernova from the first billion years of the universe

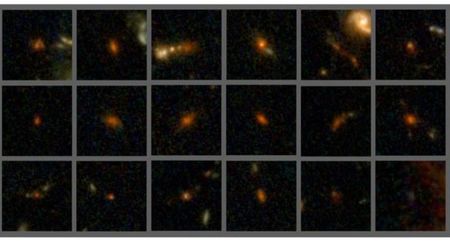

A team of astronomers employing the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has discovered the most distant exploding star to be recorded spectroscopically, giving scientists a glimpse into the early days of the universe. The findings were outlined in a paper that was published on the arXiv preprint server on January 7.

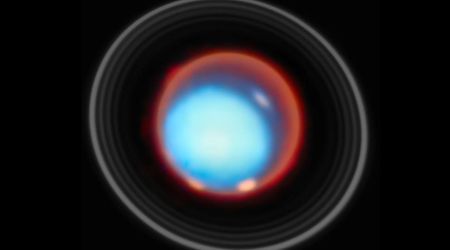

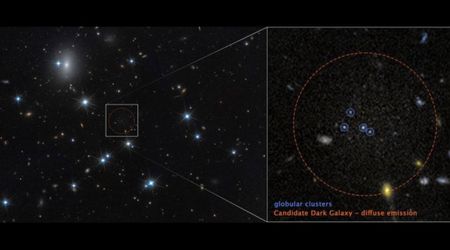

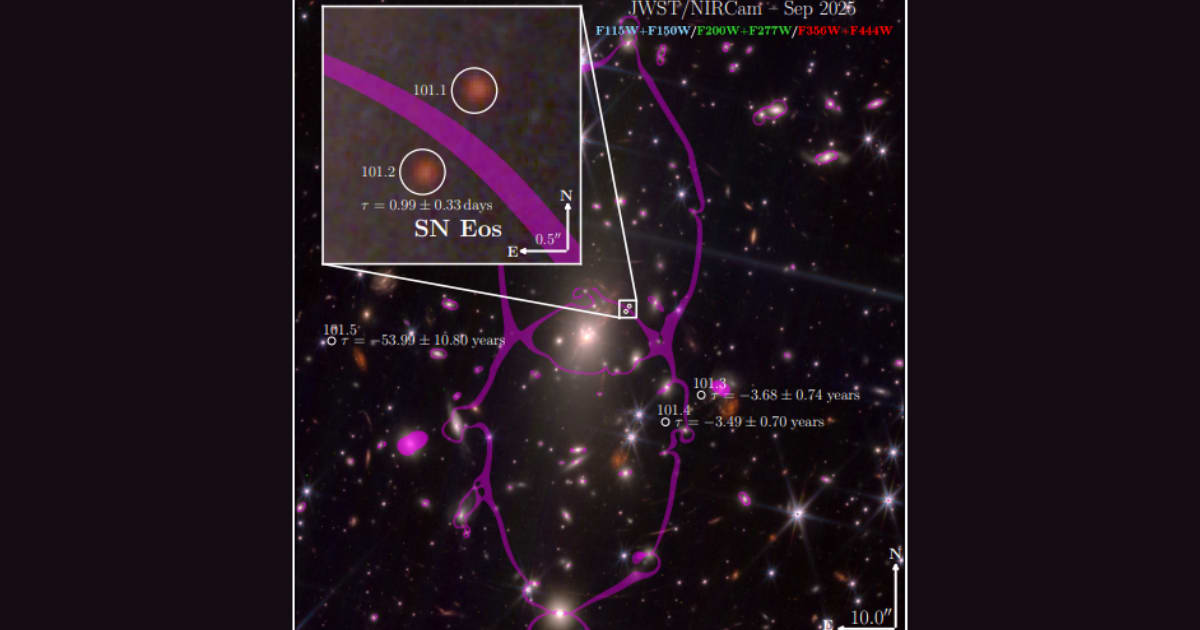

The supernova, called SN Eos, exploded when the universe was only 1 billion years old. This finding, made by David A. Coulter of Johns Hopkins University and his team of astronomers, was possible because of "gravitational lensing," a phenomenon whereby the gravity of a massive galaxy cluster causes light to bend, thus magnifying objects behind it that would otherwise be too distant or too faint to be visible, per Phys.org.

Supernovae are massive explosions that signal the death of stars. They are very important to astronomers, as they provide insights into the growth and development of stars and galaxies. SN Eos is a Type II supernova (more on this later). In particular, scientists labeled it as a "Type IIP" supernova at the end of its plateau phase. Type II-Plateau supernovae retain their brightness for an extended span of time even after reaching maximum brightness.

This finding is important for several major reasons. SN Eos has a redshift of 5.133 and resides in a galaxy that releases very faint Lyman-alpha. This is what makes it the most distant spectroscopically observed supernova. To put the value of SN Eos further into context, it is useful to examine how astronomers classify these giant explosions. According to NASA, there are two main types of supernovae, depending on whether they contain hydrogen. Type Ia supernovae usually involve a "vampire" connection between two stars. A hot white dwarf pulls matter from a nearby star until it reaches a point of no return. When it gets too heavy, the white dwarf star triggers a nuclear explosion and blows up entirely. The spectral lines of these supernovae do not show hydrogen.

The other Type II supernovae, like SN Eos, take a different route. These occur when a single, massive star runs out of fuel at the end of its life. The star's heavy iron core collapses in the absence of energy pushing outward, causing an explosion. That distinctive "fingerprint" can be seen in the light of these massive stars because they are typically encircled by a dense hydrogen atmosphere. That being said, if a massive star's stellar winds happen to blow off all the hydrogen before explosion, then it, too, will not have hydrogen in its spectral lines. Supernovae like SN Eos offer insights into the final stages of stellar evolution, and thus may help to better define existing models.

Ultimately, this discovery directly addresses the overall mission of the JWST: to enable scientists to better understand the lives and deaths of the first stars in the universe. The team has named the star after Eos, the Greek goddess of dawn, reflecting its birth in the early "morning" of the universe.