Astronomers find the earliest, hottest galaxy cluster that should not exist: 'Too strong to be real'

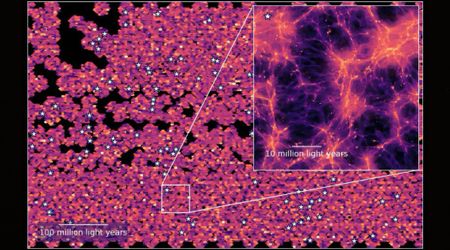

Astronomers have come across an unexpectedly intense glow from superheated gas inside the earliest known galaxy cluster, dating back to just 1.4 billion years after the Big Bang. According to current theories, the universe should not have been capable of producing something this hot so early. The discovery comes from an international team of astronomers led by Canadian researchers and was published in Nature. Their findings suggest that galaxy clusters may form faster and more violently than scientists have long believed, potentially posing a major challenge to existing cosmological models.

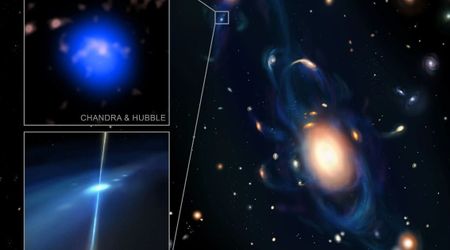

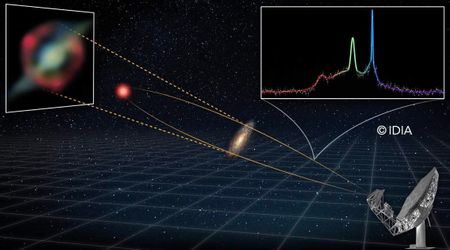

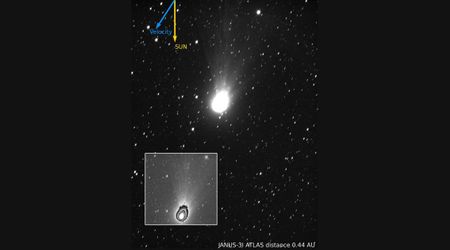

The galaxy cluster in question is known as SPT2349-56. When researchers examined it using the ALMA, which is a cluster of radio telescopes, they found gas temperatures far beyond expectations. “We didn’t expect to see such a hot cluster atmosphere so early in cosmic history,” said lead author Dazhi Zhou, a PhD candidate in the UBC Department of Physics and Astronomy, according to the University of British Columbia. “In fact, at first I was skeptical about the signal as it was too strong to be real. But after months of verification, we’ve confirmed this gas is at least five times hotter than predicted, and even hotter and more energetic than what we find in many present-day clusters.”

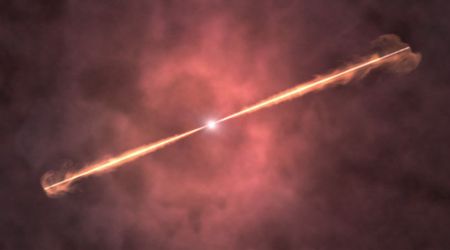

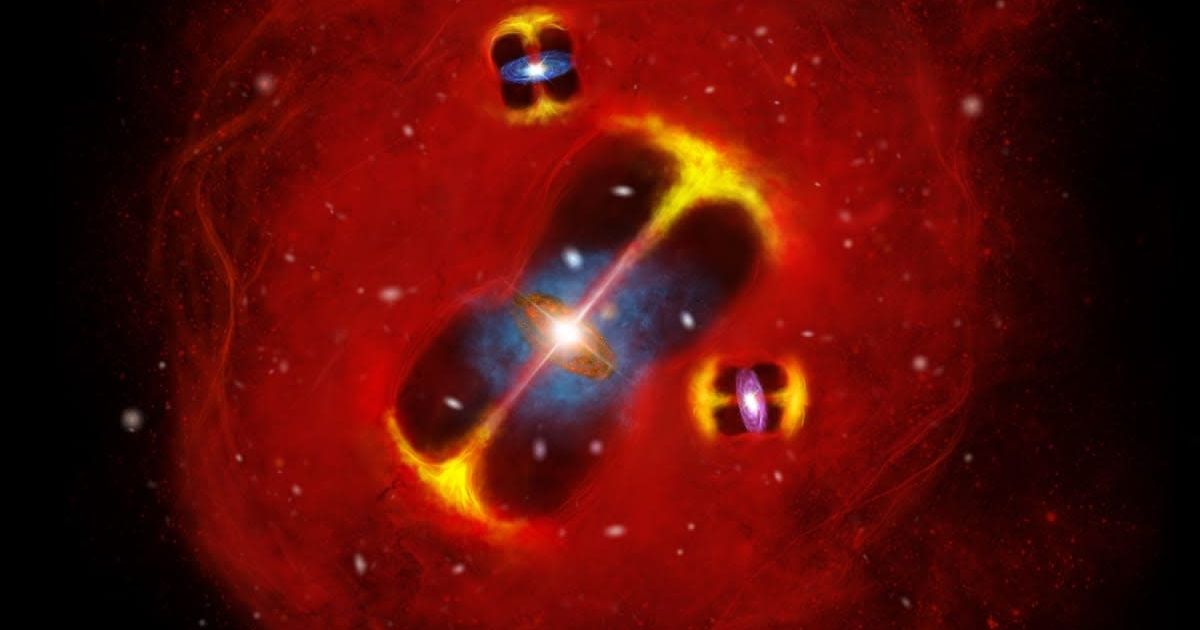

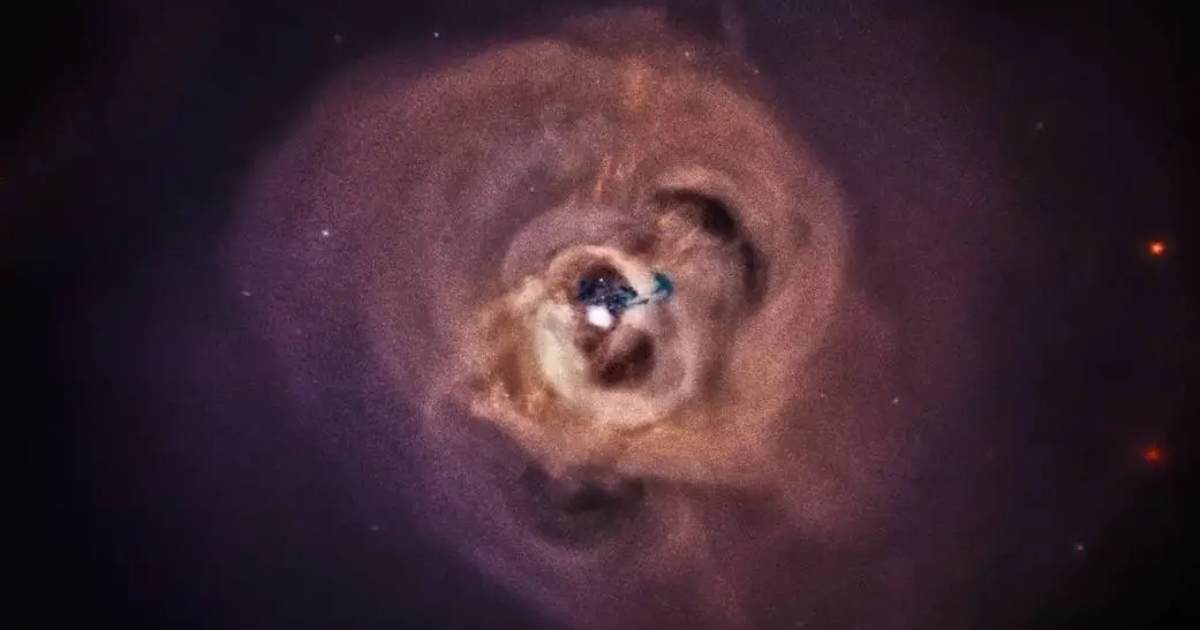

This kind of hot gas, known as the intracluster medium, fills the space between galaxies inside a cluster. In today’s universe, such extreme temperatures are usually found only in massive, mature clusters. Finding it in such a young system challenges the idea that clusters evolve slowly and calmly over time. The researchers believe the intense heat may be linked to powerful activity already underway in the early universe. “This tells us that something in the early universe, likely three recently discovered supermassive black holes in the cluster, were already pumping huge amounts of energy into the surroundings and shaping the young cluster, much earlier and more strongly than we thought,” said co-author Dr. Scott Chapman, a professor at Dalhousie University who researched while at the National Research Council of Canada.

The cluster they observed is remarkably compact and energetic. Its core spans about 500,000 light-years, similar in size to the halo around the Milky Way, but it contains more than 30 active galaxies forming stars at an astonishing rate, over 5,000 times faster than our own galaxy. The researchers relied on a technique called the Sunyaev–Zeldovich effect, which allows scientists to measure the total thermal energy of hot gas in galaxy clusters. This method helped confirm just how extreme the conditions inside SPT2349-56 truly are.

"Understanding galaxy clusters is the key to understanding the biggest galaxies in the universe,” said Dr. Chapman, who is also a UBC affiliate professor. “These massive galaxies mostly reside in clusters, and their evolution is heavily shaped by the very strong environment of the clusters as they form, including the intracluster medium.” The team now plans to study how star formation, black hole activity, and superheated gas interact and what the interaction reveals about the formation of present galaxy clusters.

More on Starlust

NASA's JWST reveals ancient monster stars that could be the ancestors of black holes

Scientists discover rare ancient 'platypus' galaxies unlike anything seen before