The Different Types of Comets Explained

Comets are cosmic snowballs of frozen gases, rock, and dust that orbit the Sun. According to NASA, there are likely billions of comets orbiting our Sun in the Kuiper Belt and even more in the distant Oort Cloud.

In many ancient cultures, the sudden appearance of a comet in the sky was often regarded with awe and sometimes fear. In the modern era, the interest in comets has shifted from superstition to scientific inquiry: Comets are considered time capsules containing primitive material left over from 4.6 billion years ago when the Sun and its planets formed.

Comets are interesting objects because of the theory of panspermia, which suggests that comets may have played a crucial role in delivering water and organic compounds to Earth, potentially seeding the planet with the necessary ingredients for life. Now think of this theory on the scale of the entire cosmos, and comets could really be considered as the “cosmic pollen” of our universe…

If you are interested in learning more about comets, keep reading as we are going to look into each type, discussing what sets each apart and what makes them unique.

Periodic Comets

Short-Period Comets

Short-period comets are characterized by their relatively brief orbital periods around the Sun, less than 200 years long. They are considered to be some of the most primitive bodies in the solar system, having remained largely unchanged since their formation.

They often follow elliptical paths that bring them closer to the Sun, leading to their periodic visibility from Earth. Due to their frequent returns to the inner solar system, short-period comets can be observed more frequently from Earth.

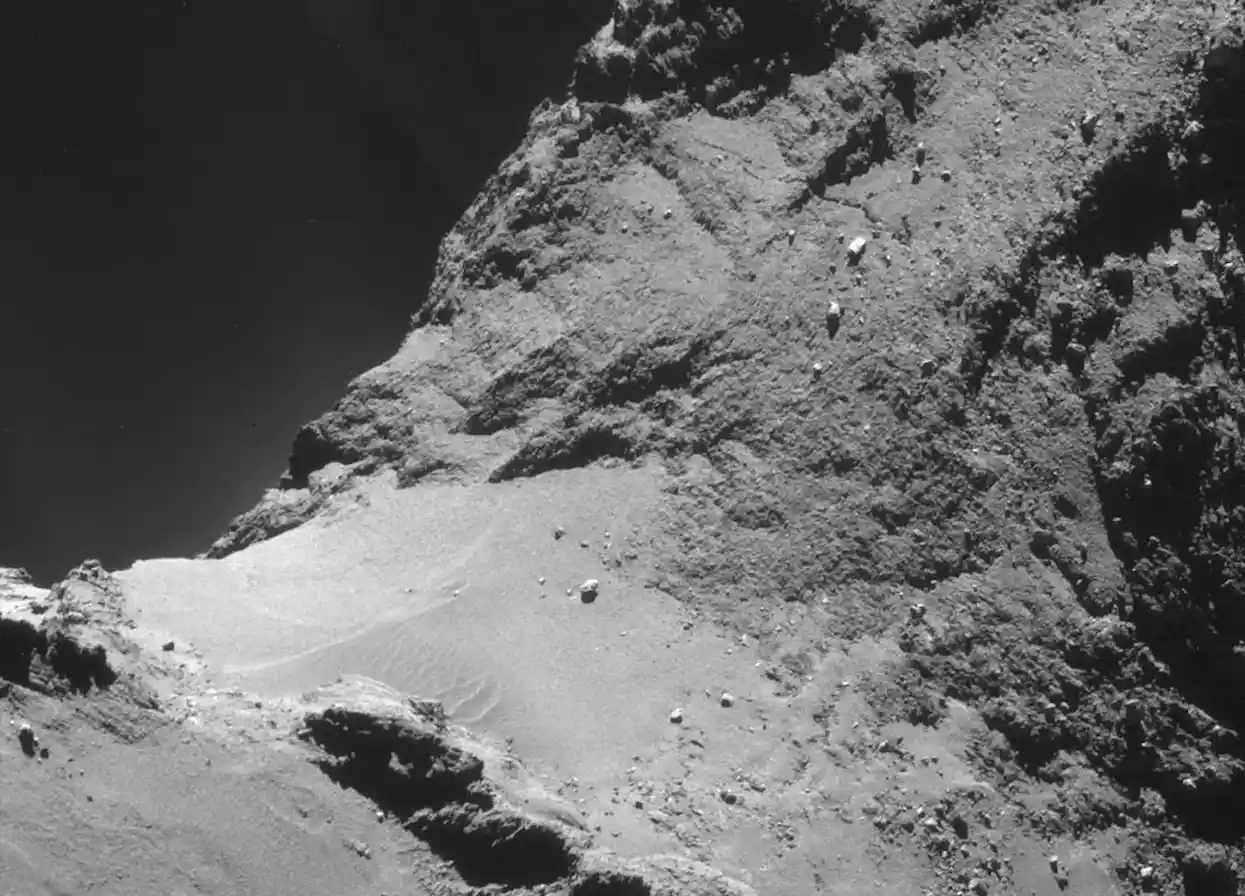

Space missions like NASA's Rosetta spacecraft, which orbited and landed a probe on the short-period comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko (see image below), have significantly advanced our understanding of this type of comet.

Long-Period Comets

Long-period comets have highly elliptical orbits that take them far beyond the orbit of Pluto, into the distant reaches of the solar system. Their orbital periods can range from 200 years to thousands of years.

Many of these comets are believed to originate from the Oort Cloud, a theoretical spherical cloud of icy bodies that lies at the very edges of the solar system, far beyond the orbit of Neptune and Pluto. This cloud is thought to contain trillions of comet-like objects.

One of the most famous long-period comets is Comet Hale-Bopp, which was visible to the naked eye for a record 18 months in 1996-1997. In November next year, stargazers around the world might catch a glimpse of a recently discovered long-period comet: Comet C/2023 A3. It depends on whether or not the comet survives its close encounter with the sun a few weeks prior. If it does and leaves the solar system intact, It will not return the system for another 26,000 years.

Non-Periodic Comets

Non-periodic comets, often referred to as single-apparition comets, are comets that do not have predictable orbits or have extremely long orbits, making their appearances in the inner solar system rare and unpredictable.

These comets are often seen only once. They have orbital periods longer than 200 years or may even be on parabolic or hyperbolic trajectories, potentially ejecting them from the solar system after their sunward journey. They are of great interest to astronomers as they are considered to be pristine remnants of the early solar system.

A famous example of a non-periodic comet is C/1992 B2 (Comet Hyakutake), which was discovered in 1996 and had an orbit suggesting it would not return for thousands of years, if ever.

Image of comet Hyakutake taken by Franz Haar - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

Sungrazing Comets

As their name suggests, sungrazing comets have orbits that bring them very close to the Sun. At their closest approach, known as perihelion, these comets can be just a few hundred thousand kilometers above the Sun's surface.

As they approach the Sun, sungrazing comets endure extreme temperatures and solar radiation. This causes their volatile materials to rapidly vaporize, creating bright tails and sometimes leading to their complete disintegration.

Sungrazing comets have been observed by various space-based observatories such as the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO). These observations provide valuable data on the composition of these comets.

For stargazers, observing sungrazing comets can be a rare treat, as only a few become sufficiently bright to be visible from Earth. In 2013, Comet ISON was highly anticipated by astronomers and the public due to predictions that it could become very bright. However, ISON met a dramatic end that epitomizes the unpredictable nature of sungrazing comets and left many of us disappointed.

Kreutz sungrazers

Kreutz sungrazers are named after the German astronomer Heinrich Kreutz, who first identified and studied them in detail in the late 19th century. Kreutz analyzed the orbits of several comets that had closely passed the Sun and realized that they shared similar orbital characteristics, suggesting they were fragments of a larger parent comet that had broken apart.

Among the Kreutz sungrazers, some have achieved the status of 'great comets,' a term we'll explore more in-depth later in this article. Notable examples include the Great Comet of 1843 and C/2011 W3 (Lovejoy).

Comet Lovejoy as seen from Santiago's nightsky. Credits: Y. Beletsky/ESO

Jupiter-Family Comets (JFCs)

After the Sun, Jupiter is the second most massive object in our solar system. This immense size and mass endow Jupiter with a powerful gravitational pull that significantly affects the trajectories and evolution of a wide range of celestial bodies, including comets.

The defining characteristic of JFCs is that their orbits have been shaped and influenced by the gravity of Jupiter. This gravitational interaction has typically pulled them into shorter orbits from the more distant parts of the solar system.

JFCs are often relatively small comets, consisting of a mixture of rock, dust, water ice, and frozen gases like carbon dioxide and methane. Some well-known JFCs include Comet 81P/Wild (Wild 2), which was visited by NASA's Stardust mission, and 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, famously studied by the European Space Agency's Rosetta mission.

When comets pass extremely close to Jupiter, they can experience intense tidal forces. These forces can sometimes lead to the comet breaking apart, as famously happened with Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 in 1994, which fragmented and collided with Jupiter.

Halley-Type Comets

Halley-type comets are a class of comets within our solar system, named after the most famous of their kind, Halley's Comet. have orbital periods ranging from 20 to 200 years. Their orbits are often highly eccentric and can be inclined at various angles to the plane of the ecliptic (the plane in which most planets orbit). They can travel in retrograde as well as prograde directions.

The most well-known Halley-type comet is Halley's Comet. It's famous for its predictable returns to Earth's vicinity every 76 years, with its last appearance in 1986 and its next expected return in 2061. The European Space Agency's Giotto mission in 1986 provided valuable data about the comet's nucleus and coma.

Extinct Comets

Simply put, an extinct comet is a comet that has lost most or all of its volatile materials, such as water ice and frozen gases. This depletion typically occurs after many orbits around the sun, where the heat causes these materials to sublimate (turn from solid to gas) and dissipate into space.

Without their volatile materials, extinct comets resemble asteroids. They are primarily made of rocky and metallic materials. This change in composition often leads to a significant decrease in brightness and activity, making them difficult to distinguish from actual asteroids.

To do so, scientists usually analyse the orbit of the object as it can give them clues about its origin. Extinct comets often have more elongated and tilted orbits compared to most asteroids.

A good example would be 1996 PW, a trans-Neptunian comet with a diameter of 6 miles (10 km). While active comets are easily spotted due to their comas and tails, extinct comets, resembling asteroids, may pose a risk as they are harder to detect and could come close to Earth without much prior notice.

Encke-Type Comets

Encke-type comets are a class of comets defined by having short orbital periods, typically less than 20 years. They are named after the comet 2P/Encke, which is one of the most famous examples and has the shortest orbital period of any known comet in the solar system at about 3.3 years.

The debris shed by Encke-type comets can lead to meteor showers on Earth. For instance, the Taurid meteor shower is associated with Comet 2P/Encke. Due to their frequent visits near the Earth and Sun, Encke-type comets are of great interest to scientists and it's not off the card for a mission to go visit this comet in the future.

Great comets

Great Comets are a specific category of comets that are exceptionally bright and can be seen clearly with the naked eye. These comets are rare, often appearing only once a decade or even less frequently.

Great Comets usually have larger nuclei and a higher content of volatile materials (like water ice, carbon dioxide, and methane) than average comets. When radiation pressure and solar wind push that dust and gas away from the comet, it creates a much larger and denser coma which in turn leads to a much longer and more visible tail, to the delight of many stargazers on Earth.

Throughout history, Great Comets have been recorded and often regarded with awe, fear, or as omens. For example, Halley's Comet, one of the most famous comets, is a Great Comet that has been observed since at least 240 BC.

Single-Apparition Comets

Single-apparition comets are comets that are visible from Earth only once, either because their orbits are extremely elongated or because they get ejected from the solar system after passing close to the Sun.

One such object was identified in 2017 by the Pan-STARRS1 telescope in Hawaii. Named Oumuamua (1I/2017 U1), this cigar-shaped comet is believed to have come from another star system. This makes it the first known interstellar object to pass through our solar system.

It was moving so fast and was on such a hyperbolic trajectory that astronomers knew it would leave our solar system soon. It was visible only for a brief period, making detailed study challenging.

Artist rendition of the Oumuama comet. Credits: By Original: ESO/M. Kornmesser Derivative: nagualdesign (from an earlier version by Tomruen) (c.f. Masiero; Meech et al.

Lost comets

Lost comets are comets that were once observed and recorded but then became unobservable or were not seen again for various reasons. Its orbit might be altered by gravitational interactions with planets or other celestial bodies, making its predicted path inaccurate. Some might slowly break apart, often due to losing their ice and gasses over decades. Lastly, it could simply be that early observations and calculations might have been inaccurate, leading to incorrect predictions about the comet's future position.

One such comet is Comet Westphal, which was first observed in 1852, and then subsequently again in 1913. It was expected to appear again in 1976 but scientists could not find it.

Hyperbolic comets

A hyperbolic comet is one that has an orbit with an eccentricity greater than 1. In simpler terms, this means the orbit is not closed or elliptical but instead is an open-ended path, resembling a hyperbola. Such comets are on a one-time visit to the inner solar system, never to return again. As these comets approach the inner solar system, they are often accelerated by the Sun's gravity, reaching high speeds.

C/1980 E1 (Bowell) is one of those escaping comets: After passing near Jupiter in 1980, its orbit was altered to a hyperbolic trajectory, effectively ejecting it from the solar system. Some of these hyperbolic comets, such as1I/2017 U1 'Oumuamua, can be interstellar in origin, having entered our solar system from elsewhere in the galaxy.

Main-belt comets (MBCs)

Main-belt comets (MBCs) are a relatively recent classification in the study of small solar system bodies. MBCs are found in the asteroid belt, a region located between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter.

MBCs are unique in that they orbit within the main asteroid belt but exhibit cometary features, such as outgassing, which suggests the presence of volatile materials including water.

The dynamic history of the Solar System indicates that there was significant movement and mixing of celestial bodies during its formation. This means that objects from the main asteroid belt, including MBCs, could have been scattered inward toward Earth. Such scattering events, possibly during periods like the Late Heavy Bombardment, could have resulted in water-rich bodies impacting the early Earth.

Our understanding of these objects is still developing and more in-depth studies, both observational and theoretical, are needed to better understand them. The International Space Science Institute has a team of researchers dedicated to figuring out MBCs and they have released a paper on the subject if you are interested in learning more: The Main Belt Comets and Ice in the Solar System

So, where do comets come from?

Those icy bodies are remnants from the early and rather violent formation of the solar system. In different circumstances, some of those comets could have been absorbed by protoplanets and become part of the 8 planets we now have in our system.

Instead, and due to the intricate gravity balance of the solar system, they ended up in mainly two places in the system: The Kuiper Belt and the Oort Cloud. The Kuiper Belt is a vast region of space beyond the orbit of Neptune, about 30 to 55 astronomical units (AU) from the Sun. The Oort Cloud is a hypothetical, gigantic spherical shell surrounding the solar system. It's believed to be located about 2,000 to 100,000 AU from the Sun.

Those two locations are known to be “cometary reservoirs” and over time, gravitational interactions can push some of these comets into the inner solar system. New Horizons, a spacecraft designed to pay Pluto a visit, has now got the updated mission of studying objects in the Kuiper belt.