Scientists recreate the ocean of Saturn's icy moon Enceladus in lab

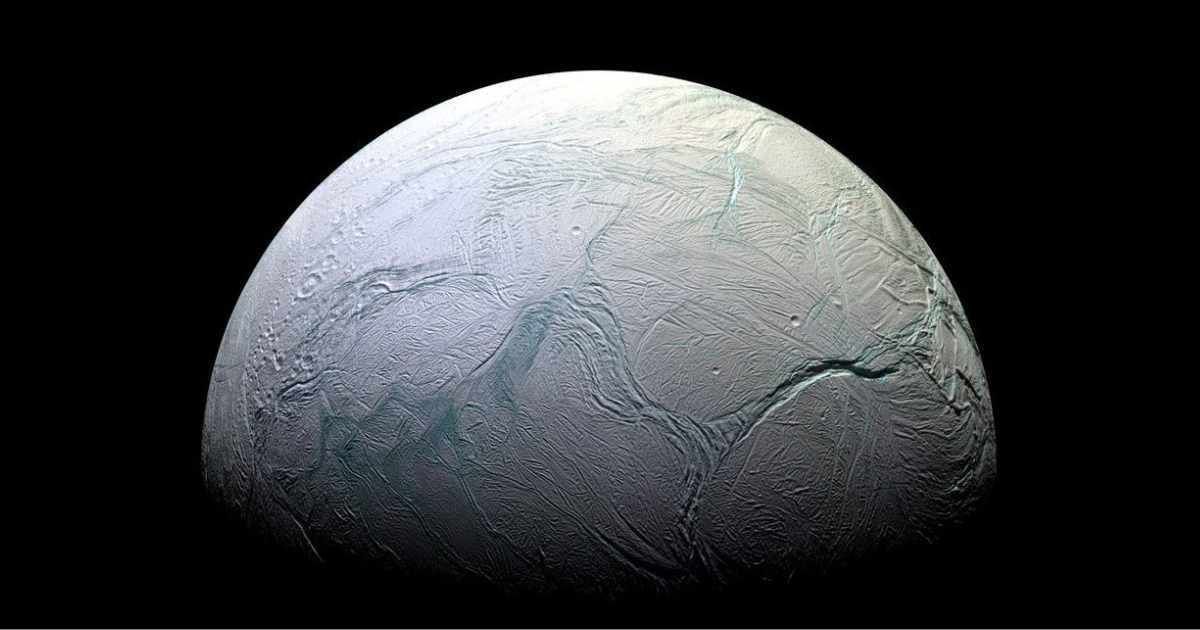

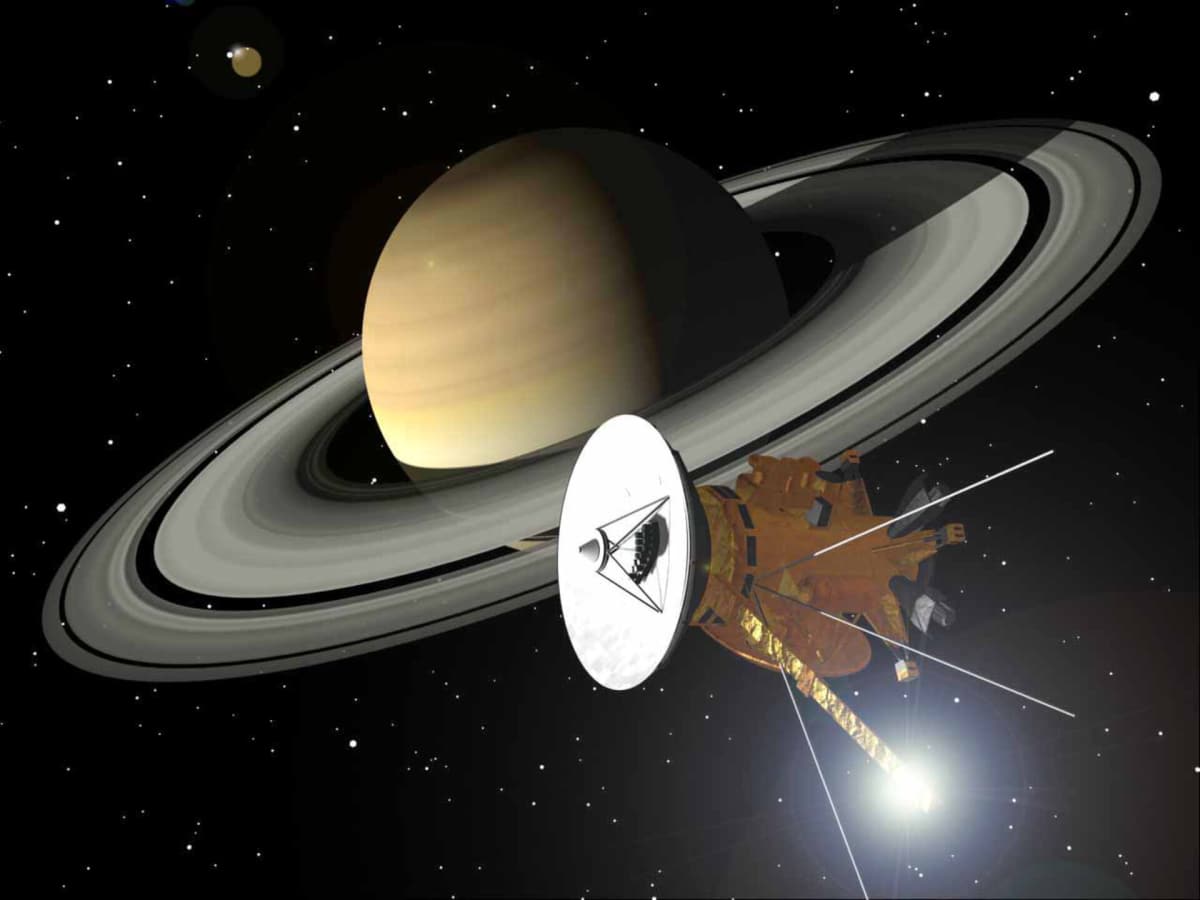

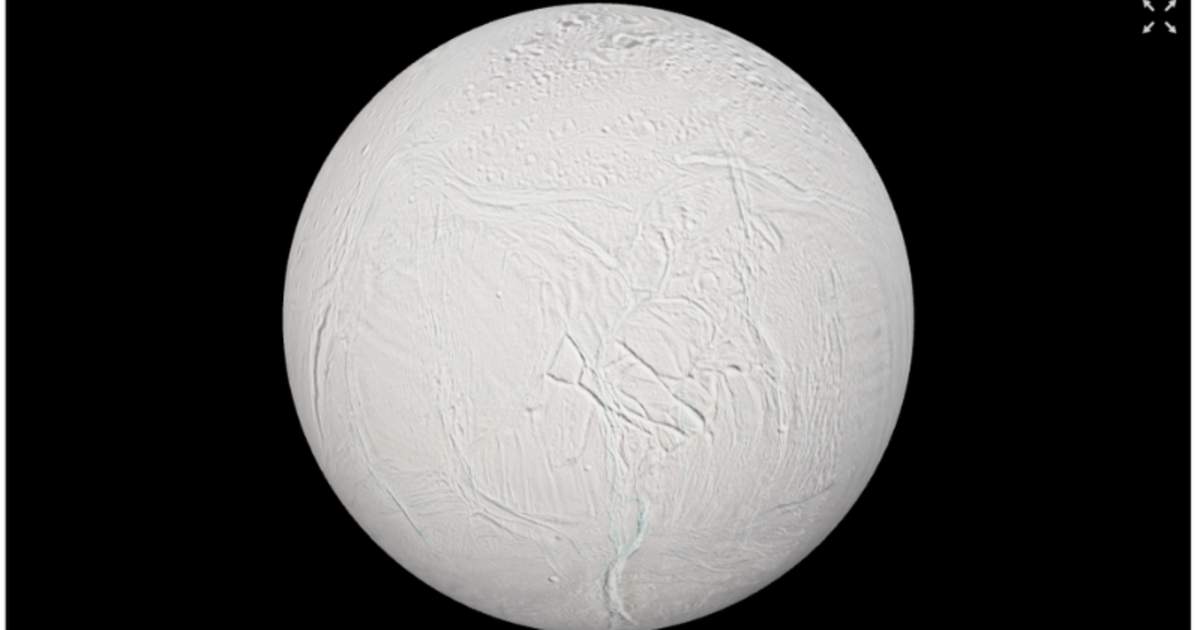

Enceladus, no wider than Arizona, is an icy moon of Saturn. It has a global subsurface ocean. NASA’s Cassini spacecraft has detected signs of organic molecules in water-rich plumes that rise skyward from cracks near this moon’s South Pole. In those plumes, the spacecraft found something extraordinary: organic molecules that could make building blocks of life. But, where do those organic molecules come from? Does Enceladus churn them out or inherit by birth? Researchers in Japan and Germany recreate Enceladus-like conditions in a lab, and they confirm that the icy moon is actively producing life-forming organic molecules in its icy ocean, according to a study published in Icarus.

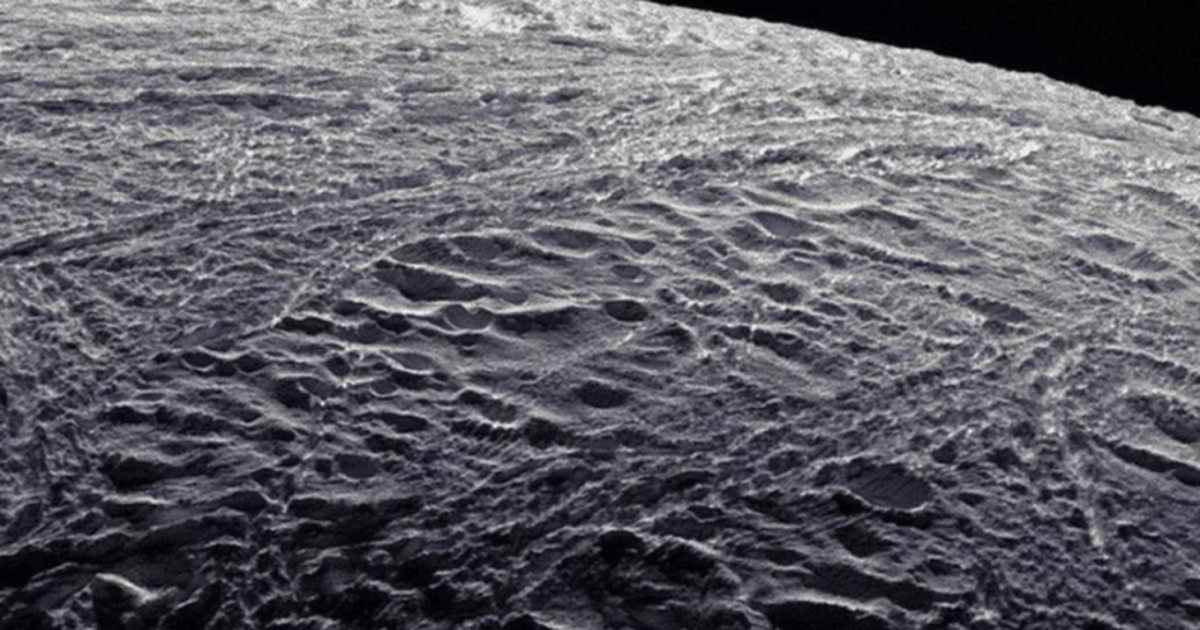

Between 2004 and 2017, Cassini circled Enceladus several times and analysed its icy, water-rich plumes closely. It detected various inorganic and organic compounds that range from carbon dioxide to larger hydrocarbons, which we know coalesced to form complex biomolecules on Earth. But does this currently happen on Enceladus? To know the answer, Max Craddock at the Institute of Science Tokyo and his teammates from Germany set out to find a link between ocean chemistry and spacecraft observations. Using a high-pressure reactor, the scientists recreated mini oceans and exposed them to conditions thought to exist inside the moon. They created hot, pressurized water reaching 150°C that mimics hydrothermal vents, deep freezing, down to –40°C, like seawater trapped in ice, and cycles of heating and freezing, simulating long-term movement between ocean and ice shell. Products made through such simulations were then analyzed using a laser-based mass spectrometer designed to mimic Cassini's Cosmic Dust Analyzer.

The hydrothermal experiments consistently generated amino acids such as glycine, alanine, serine, and nitrogen-bearing compounds, indicating that simple building blocks of life can form under Enceladus-like conditions. Higher temperatures led to higher yields, but even modest heating was enough to trigger rich chemistry. Long-term freezing produced glycine, the simplest amino acid. Many of these chemicals closely resembled the smaller organic compounds observed by Cassini's spectroscopic instruments. But the researchers couldn’t produce some of the larger molecules detected by Cassini.

Although amino acids formed easily in the lab, signatures of these molecules are missing in Cassini’s data. The researchers say that amino acids may be hidden inside salty ice grains, making it difficult for the spacecraft to spot them. However, their results clearly show that Enceladus' subsurface ocean is actively cooking up life-brewing organic molecules. "For future missions, this sharpens how plume measurements should be interpreted and underscores the importance of instruments capable of verifying amino acids and resolving whether complex organics reflect ongoing chemistry or ancient material," Craddock said in a statement.

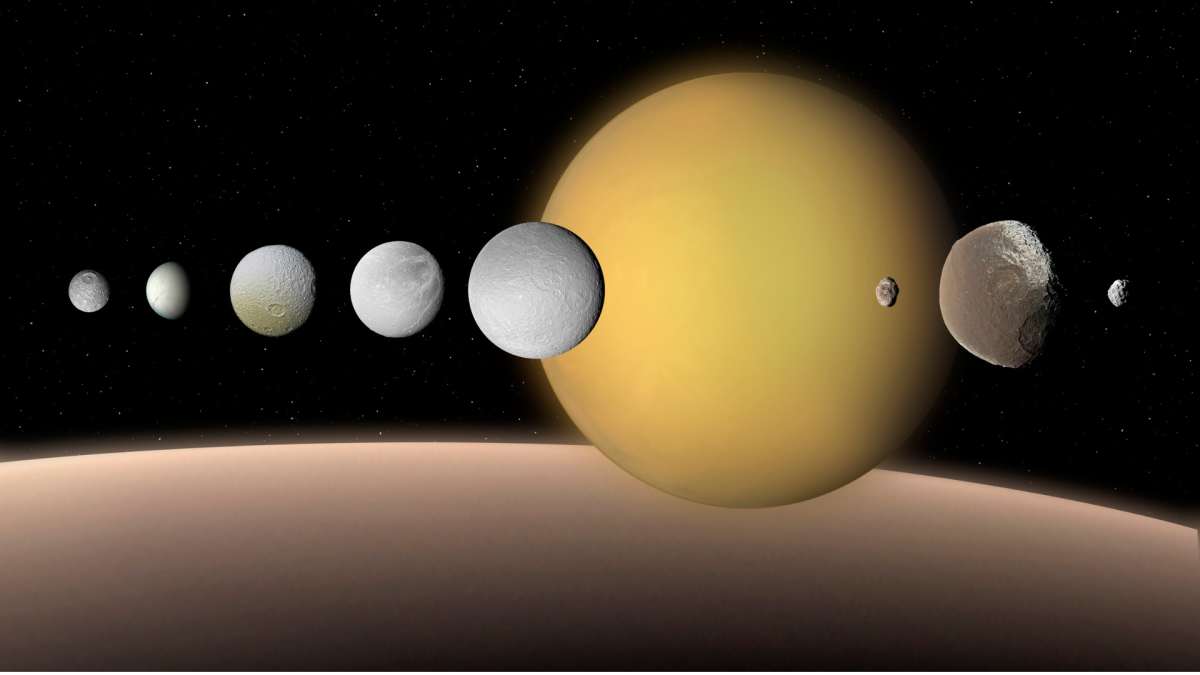

Life on Earth as we know it evolved primarily in the ocean, suggesting the need for life to evolve. Yet, it is not known whether Enceladus has all the favorable conditions for life, and we are uncertain about the ages of Saturn’s moons, which range from 2 to 4.5 billion years. With no future missions to Enceladus in sight, laboratory simulations seem the right option to extrapolate about its chemistry and the prospect of life.

More on Starlust

How long would it take to reach Saturn

NASA observes peculiar red glowing formation floating on Saturn's biggest moon