NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope observes young star ejecting common Earth crystals

![JWST’s 2024 NIRCam image shows protostar EC 53 circled. [Cover Image Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, STScI, Klaus Pontoppidan (NASA-JPL), Joel Green (STScI); Image Processing: Alyssa Pagan (STScI)]](https://d3hedi16gruj5j.cloudfront.net/788660/uploads/ac27edb0-f852-11f0-9beb-d5b54da9e2cb_1200_630.jpeg)

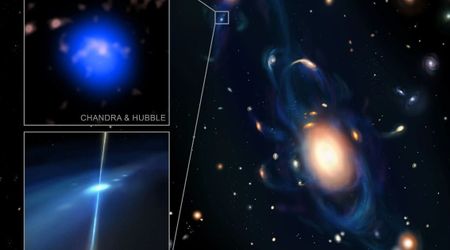

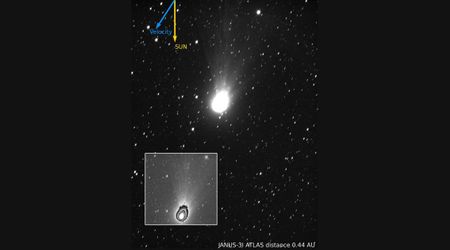

A protostar designated EC 53 residing in the Serpens Nebula, about 1,300 light-years from Earth, has been captured by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope and has answered a difficult question: How do comets on the margins of our solar system harbor crystalline silicates that require immense heat to form?

Go with the (silicate) flow

— NASA Webb Telescope (@NASAWebb) January 21, 2026

Webb’s observations of the protostar EC 53 uncovered long sought evidence to explain why comets at the edge of our solar system contain crystalline silicates, a common ingredient found on Earth. https://t.co/w4D5gDmpMq pic.twitter.com/7MWLL8EeXA

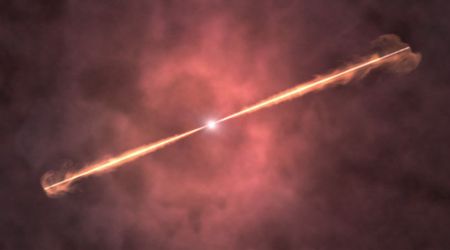

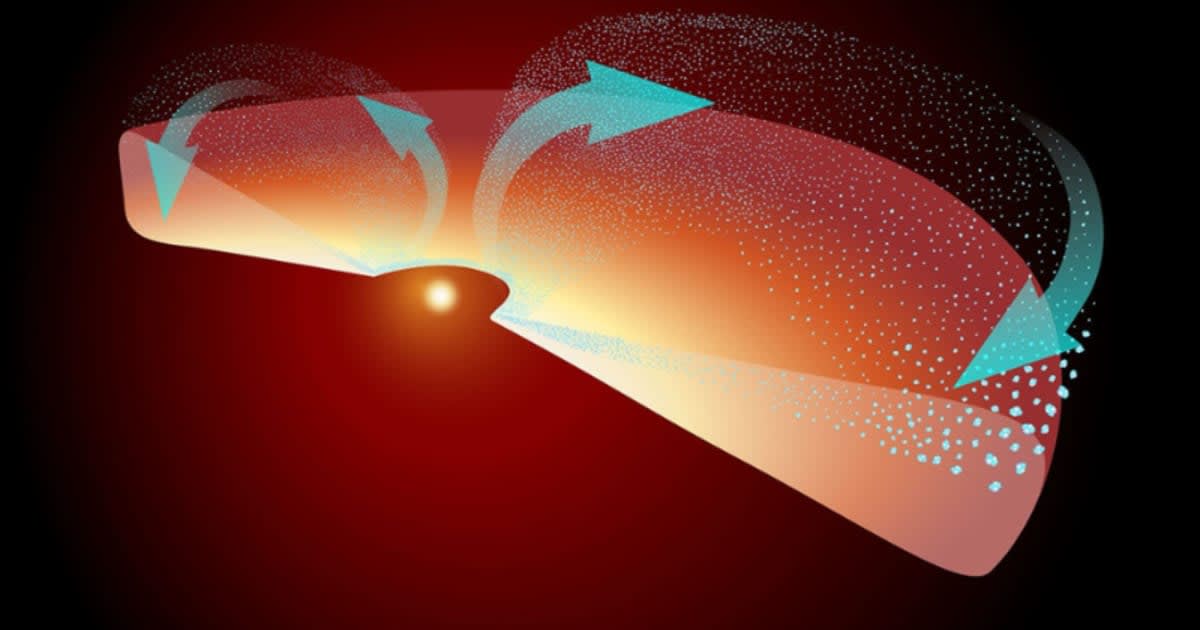

EC 53 is believed to have similar conditions to those in the early stages of our Sun, surrounded by a disk of gas and dust where planets take shape. It is in the hot inner part of the disk that crystalline silicates are formed. The star seems to follow an 18-month cycle. Every cycle, it enters a 100-day "bombastic burst" phase, pulling in gas and dust from its disk while blasting out narrow, high-speed jets that the researchers think carry the crystals to the outer edges of the protoplanetary disk. The lead researcher for the paper published on January 21, 2026, Jeong-Eun Lee from Seoul National University, called it a "cosmic highway," carrying fresh crystals to sites of active comet formation.

JWST's Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) captured EC 53 in times of both calm and intense outburst periods and also collected two sets of detailed spectra, which helped in pinpointing exact silicate types and their locations. Co-author Doug Johnstone from Canada's National Research Council said, "Even as a scientist, it's amazing we can detect specific Earth minerals like forsterite and enstatite out there. These are common minerals on Earth. The main ingredient of our planet is silicate."

For years, astronomers scratched their heads over crystalline silicates in our solar system's comets. These "dirty snowballs" assemble in ultracold voids, yet harbor crystals demanding intense heat in order to be formed. These crystalline silicates had also been detected in protoplanetary disks around older stars, but no one could confidently identify the transport method. In this instance, Webb and the research led by Jeong-Eun Lee helped connect the dots. Instrument scientist Joel Green at the Space Telescope Science Institute, who's also a co-author of the study, hailed the telescope's precision: "It’s incredibly impressive that Webb can not only show us so much but also where everything is."

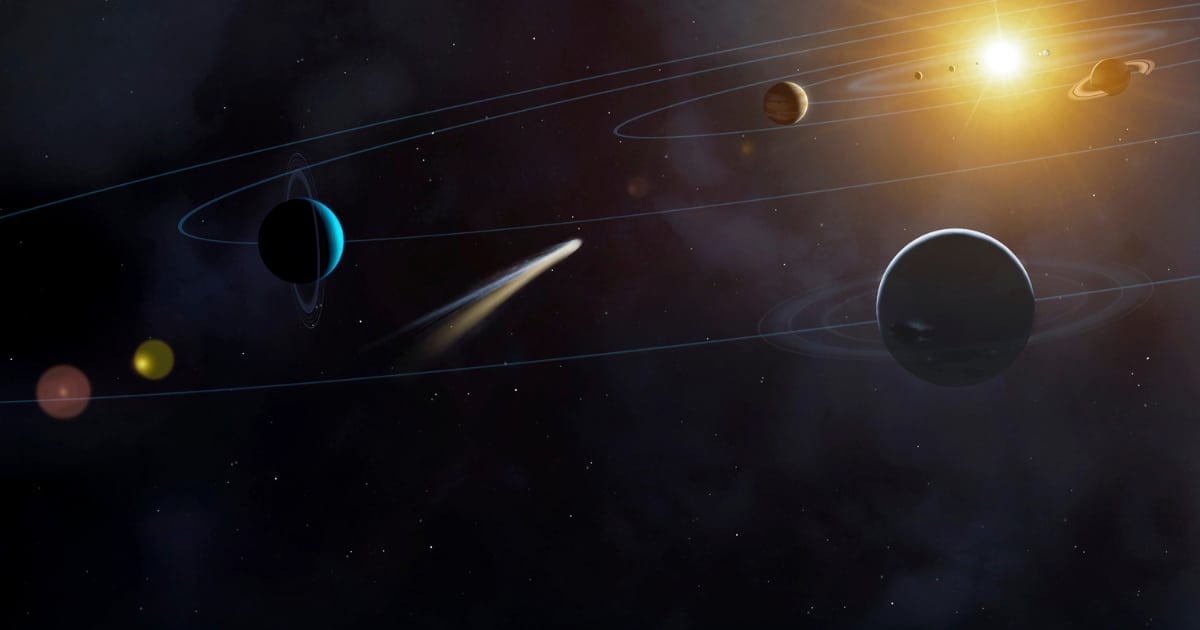

EC 53 will be engulfed by dust for another 100,000 years before it is expected to mature and give birth to gas giants and any possible rocky planets. Once the disk has settled and both the star and planets are fully developed, there will be a planetary system with a Sun-like star at its center and crystalline silicates "littered" throughout that remains. Led by NASA alongside ESA and CSA, JWST continues to examine distant worlds and stars to give us a better sense of our own place in this massive, ever-mysterious universe.

More on Starlust

NASA's James Webb Space Telescope pictures Helix Nebula in extraordinary detail

The mystery behind 'little red dots' discovered by James Webb Telescope has finally been solved