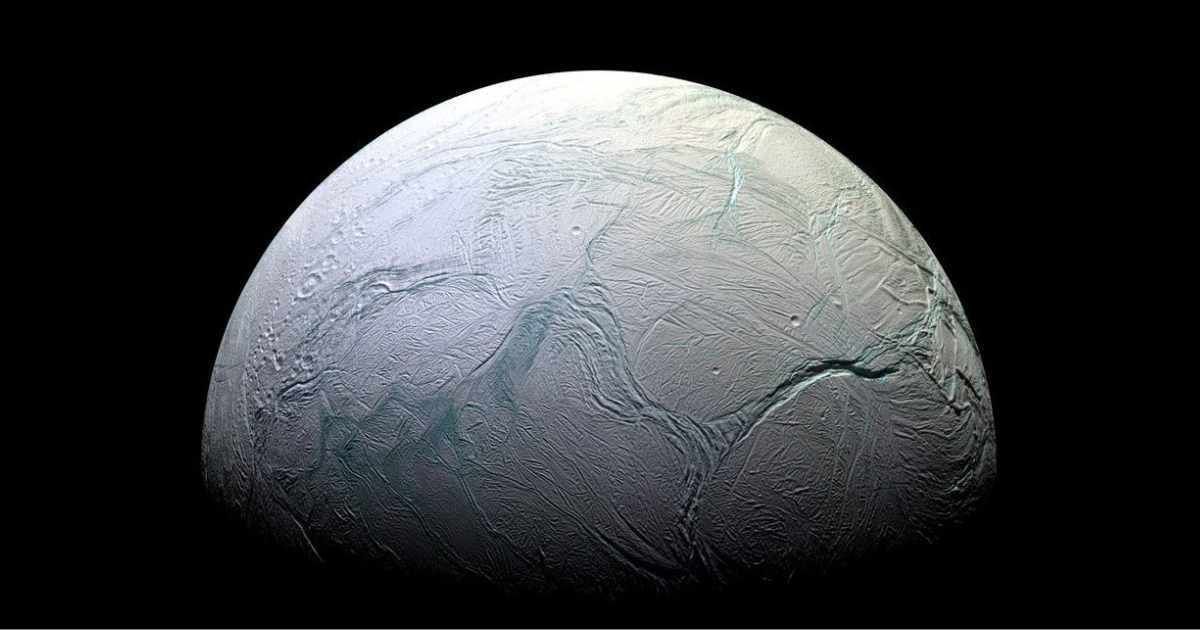

Groundbreaking data from NASA’s Cassini suggests Saturn's icy moon could support life

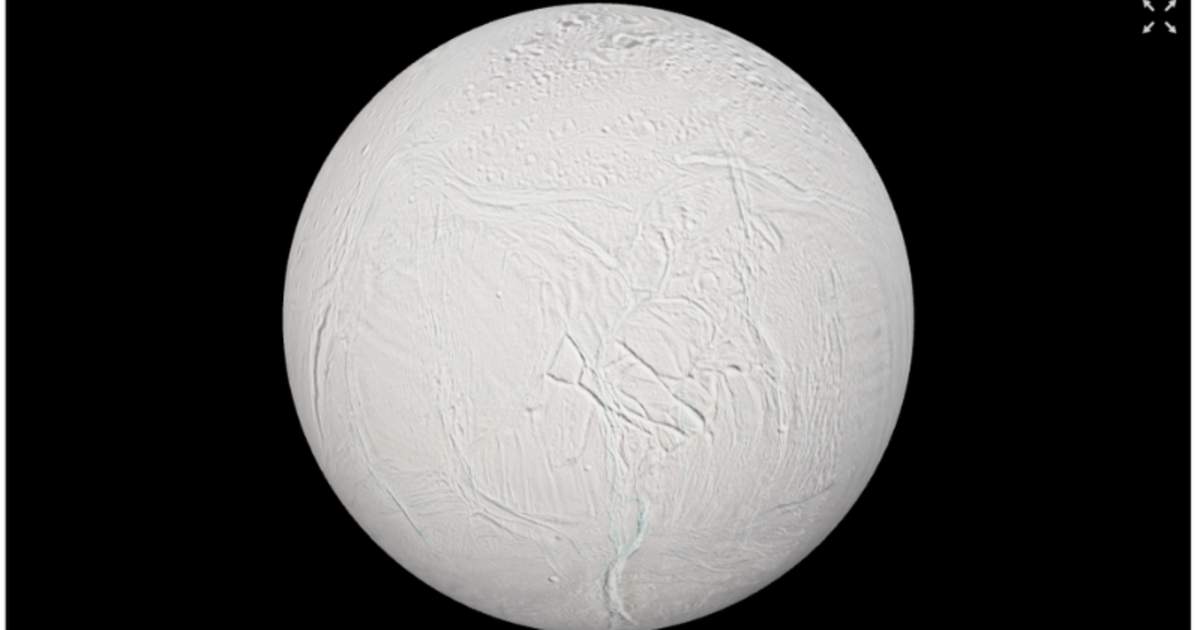

A recent study of data from NASA’s Cassini spacecraft has revealed groundbreaking findings about Saturn's icy moon Enceladus, suggesting that it may have a stable ocean capable of supporting life. Per the University of Oxford, the study, titled ‘Endogenic Heat at Enceladus’ North Pole’, published in Science Advances, has confirmed that more heat is being released from Enceladus than what would be expected from a passive body, thereby supporting the theory that life could survive on the moon.

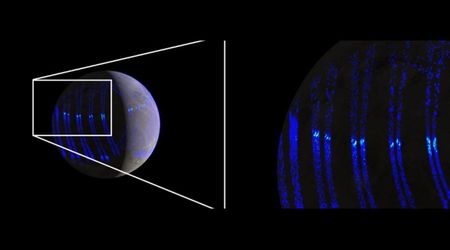

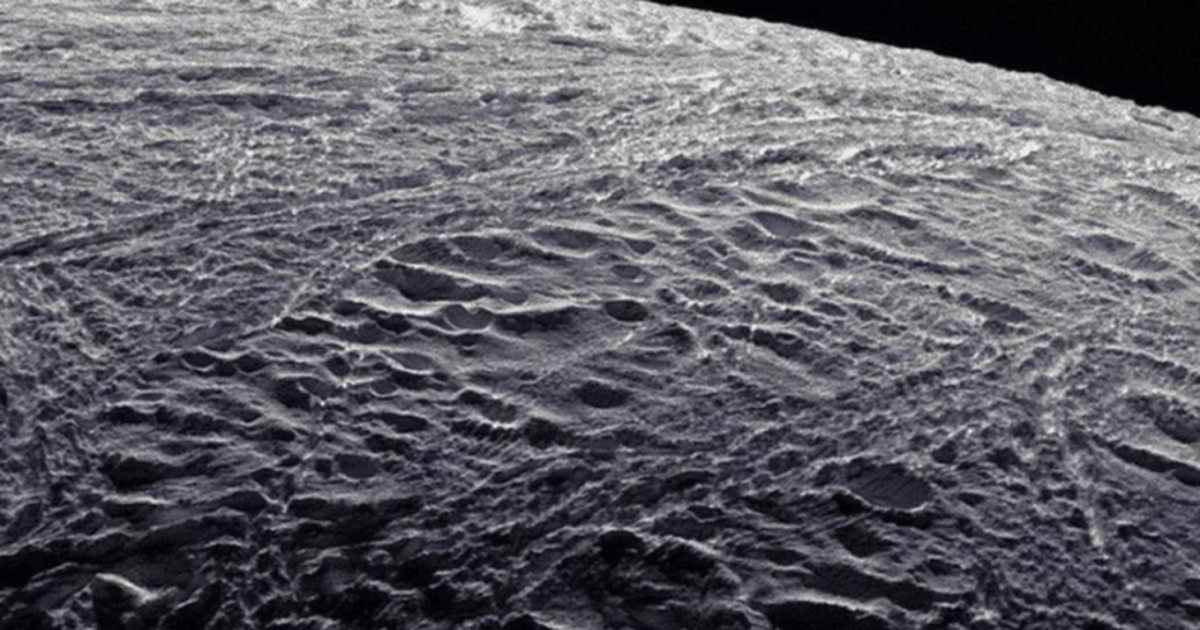

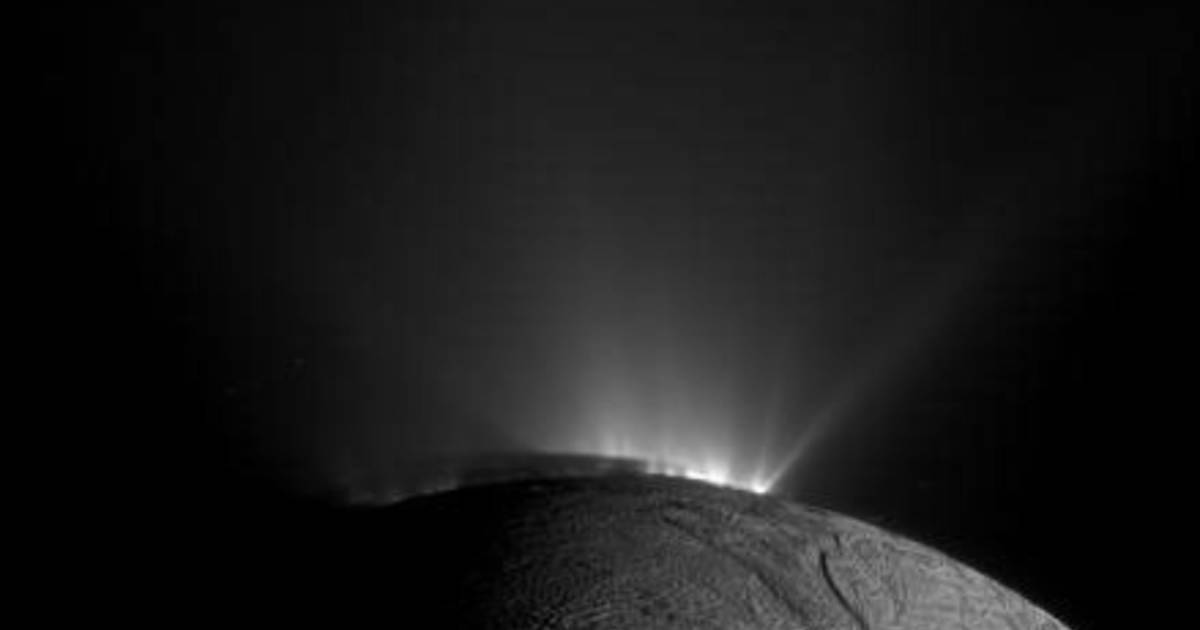

Its salty sub-surface ocean, which scientists believe is the source of its heat, makes it favourable to look for signs of life. But for it to actually support life, it will have to have an energy balance. The phenomenon responsible for maintaining said balance? Tidal heating caused by Saturn's gravitational pull. As it orbits Saturn, the moon is pulled and pushed, generating internal heat that keeps its ocean in a liquid state. Until now, it was assumed that Enceladus was only losing heat from its south pole, where dramatic plumes of water ice and vapor erupt from the surface.

But now, new data from the Cassini spacecraft show that the north pole—previously considered to be geologically inactive—is also emitting heat. Researchers from the Southwest Research Institute, Oxford University, and the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona, collaborated for this study. Together, they look at the north polar data from two different seasons—deep winter (2005) and summer (2015). The aim was to find out how much energy the satellite lost from its warm (0°C, 32°F) subsurface ocean. Then, by comparing the data from the Cassini Composite InfraRed Spectrometer (CIRS) with their estimate of the polar night surface temperature, the researchers found that the north pole was about 7 K warmer than expected, suggesting that the cause is the ocean below.

![An infographic illustrating Enceladus' energy balance [Image Credit: University of Oxford/NASA/JPL-CalTech/Space Science Institute (PIA19656 and PIA11141)]](https://de40cj7fpezr7.cloudfront.net/8214efda-c3c9-4c2f-b2b3-0e2e8ad719c5.jpg)

While the heat flow of 46 milliwatts per square meter may seem small, it’s actually about two-thirds of the heat loss per unit area from Earth’s continental crusts. The total conductive heat loss from Enceladus amounts to about 35 gigawatts, roughly equal to the output of 66 million solar panels or 10,500 wind turbines.

If the previous data from the south pole is taken into consideration, the total heat loss from Enceladus is estimated to be around 54 gigawatts, closely matching the predicted energy input from tidal heating. This balance between heat loss and gain strongly suggests that Enceladus’ ocean could remain liquid for long periods of time, offering suitable conditions for life. “Understanding how much heat Enceladus is losing on a global level is crucial to knowing whether it can support life,” said Dr. Carly Howett, corresponding author of the study. “It is really exciting that this new result supports Enceladus’ long-term sustainability, a crucial component for life to develop.” The study also provides insights into the thickness of the ice shell, which is crucial to exploring Enceladus' ocean.

Lead author Dr. Georgina Miles added, “Our study highlights the need for long-term missions to ocean worlds that may harbor life. The data might not reveal all its secrets until decades after it has been obtained.”

More on Starlust

NASA observes peculiar red glowing formation floating on Saturn's biggest moon