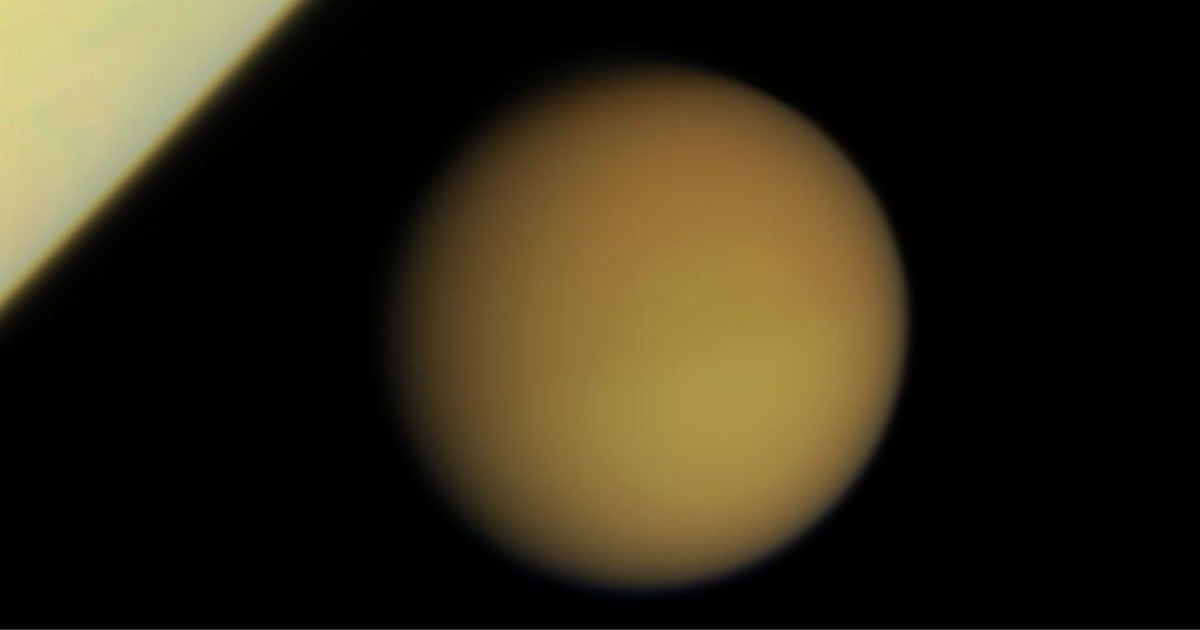

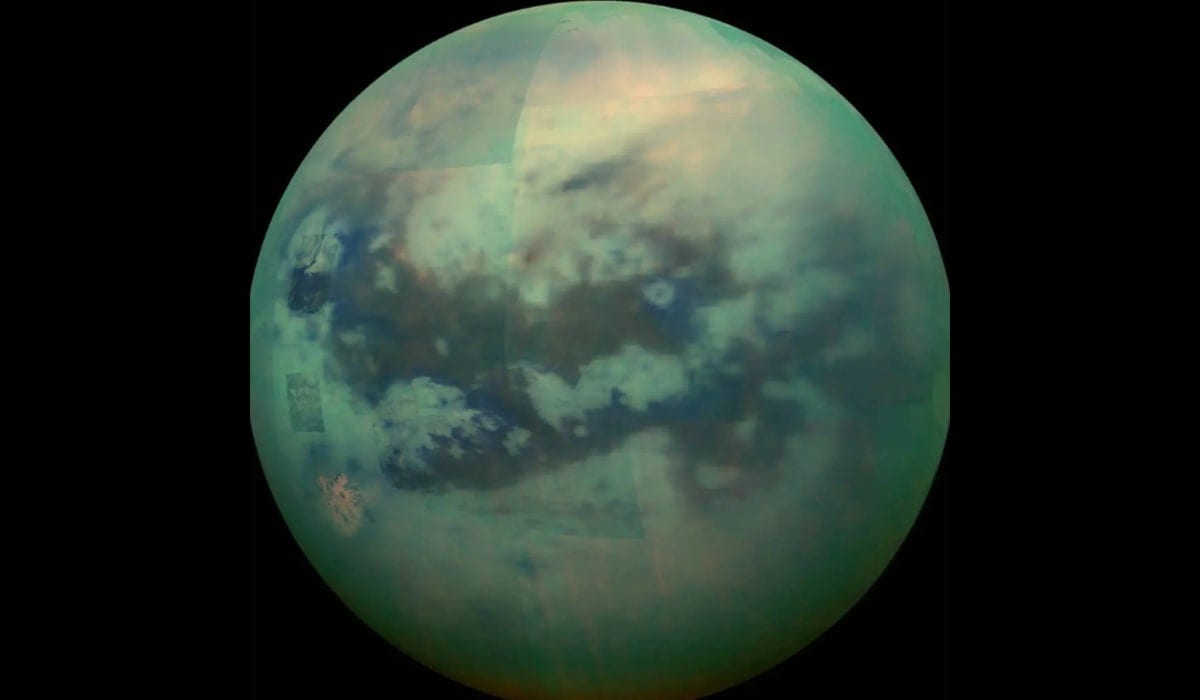

Does Saturn's moon Titan really have an underground ocean? New study raises doubts

New evidence suggests that a large, hidden ocean may not exist on Saturn's largest moon, Titan, after all. Instead of a deep, worldwide sea, scientists now believe that the interior of the moon is actually composed of slushy ice with pocket regions of water. The study, published December 17 in the journal Nature, disputes previous assumptions about the composition of the solar system's most Earth-like moon.

The manner in which Titan flexes under its host planet's gravity indicates that it has a vast underground ocean. However, planetary scientists at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory recently re-examined the moon by using more precise analysis techniques. They found that Titan is much stiffer than scientists believed. Instead of a fluid ocean, the moon has a layer of ice that is close to its melting point and yet is being kept from liquefying by high pressure. This slushy layer likely has small, isolated reservoirs of liquid water.

Lead researcher Flavio Petricca told Space.com that though Titan might have started with an ocean, it likely froze over time. The moon's core may have lacked the radioactive heat necessary to keep such a large volume of water from turning to ice. "Ocean worlds may be less common than recently thought," the researchers noted—a nod to a subtle shift in how astronomers view the potential for life in our solar system.

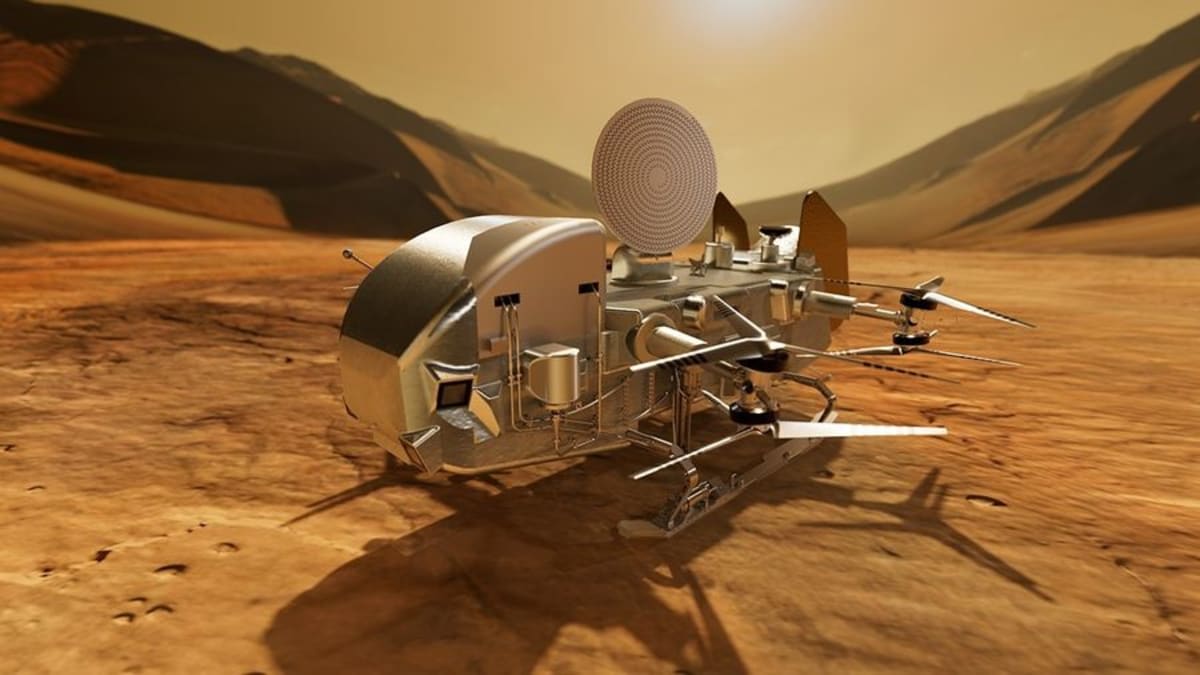

The discovery opens up new questions about the possibility of life on Titan: while a global ocean is widely regarded as one of the best environments for biology, nobody knows whether smaller, disconnected pockets of water can serve the same purpose. Scientific eyes are now shifting to NASA's imminent Dragonfly mission. Due to arrive on Titan in the mid-2030s, the robotic rotorcraft will survey the moon's geology and provide a better understanding of what lies beneath the surface.

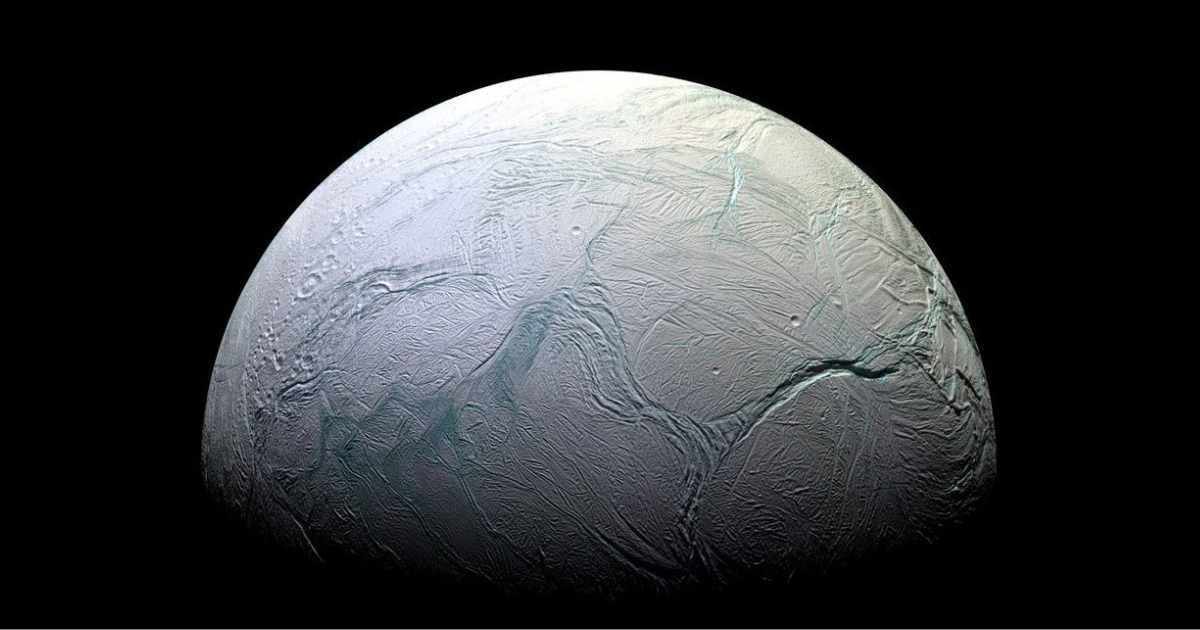

While the prospects for a global ocean on Titan slowly fade, another of Saturn's moons is showing much more promise. A separate study, published in Science Advances, suggests that Enceladus may have exactly what Titan lacks: a stable, warm, and active ocean. Researchers found Enceladus is producing far more energy than expected by analyzing the heat signatures at the moon's North Pole. That heat is likely produced by "tidal heating," where Saturn's intense gravity perpetually squeezes and then stretches the moon as it orbits. The cosmic tug-of-war creates internal friction, enough to keep the subsurface water from freezing.

The discovery of Enceladus, thus, is a big win for astrobiology. Unlike Titan, which at best may have water trapped in isolated pockets, Enceladus appears to have a uniform energy balance. This circulation of heat and liquid water makes it one of the most propitious places in the solar system to hunt for signs of life. Up until now, researchers thought this heat was only escaping through the moon's South Pole, where giant plumes of water vapor spray into space. The new evidence of heat at the North Pole suggests the moon's internal engine is much more powerful and widespread than earlier data indicated.

More on Starlust

Here's how you can spot Saturn's moons: Titan, Rhea, Dione and more

NASA observes peculiar red glowing formation floating on Saturn's biggest moon