Spring Constellations: Navigating the Star Asterism In March, April, and May

Last Updated: August 25, 2023

There’s always something happening in the night sky, but the changing of seasons is a particularly great time to go stargazing. Let’s go over stargazing tips and the main constellations for March, April, and May including what they look like, how to find them, and their brightest stars.

Constellation Guide

Let’s dive into the details of the constellations featured this season. Stars and Messier/ Deep-Sky Objects will be listed in order of brightness with the brightest first.

We’ll feature a few constellations that should be visible throughout the whole season and even throughout the year in your hemisphere. The constellations appear to rotate around the poles meaning that the ones very close to the pole will be high enough in the night sky that they are generally visible throughout the year for that hemisphere besides times when they are particularly close to the horizon and therefore susceptible to being blocked.

In general, these are good starting constellations as they are always visible and fairly easy to find, providing a good starting point to line up with other constellations. There are other circumpolar constellations, but these are considered particularly easy to find and featured during these months.

Then we will go through the constellations typically featured for each month in March, April, and May.

Featured Circumpolar Constellations

Ursa Major (the Great/ Big Bear)

Ursa Major is one of the most well-known and recognized constellations in the world and certainly in the Northern Hemisphere as it contains the famous Big Dipper asterism which points the way to our pole star (in Ursa Minor) by elongating the line created by the two stars at the far right end of the Dipper. Other stars connect to the front of the Big Dipper to create the torso, head, and front legs of the bear, but the stars are fainter than the Big Dipper stars.

This constellation is one of the oldest constellations, dating back as far as 13,000 years ago, and is mentioned in the Bible and in works by Homer. It is one of the original 48 constellations cataloged by Greek astronomer Ptolemy in the 2nd century and is associated with several different Greek and Roman myths. The most cited one is that Callisto, a nymph was turned into a bear by Hera, Queen of the gods, as revenge for the affair with Zeus, her husband and King of the gods. The reason why it has a long tail is that Zeus grabbed Callisto the bear by the tail and lassoed her around him, elongating it, before he launched her into the night sky.

The collection of stars making up Ursa Major has also taken different forms in different cultures. It is Saptarshi, with the the brightest stars representing the Seven Sages, in Hindu legend. The Chinese believed the seven bright stars represented the Government, Tseih Sing, or the Northern Measure, Pih Tow. In some Native American stories, the three stars in the handle of the Dipper represented three warriors chasing a great bear instead of the bear having a long tail. In South Korea, the constellation is referred to as the Seven Stars of the North. During the Civil War, slaves escaping the South were told by members of the Underground Railroad to follow the “drinking gourd” to help them navigate north.

Ursa Major is the 3rd largest constellation in the night sky with an area of 1,280 square degrees with several very bright stars. Below are those that are under a magnitude of 3 in order of brightness.

- Alioth “Black Horse” is the third star down the tail of the bear/ ladle of the Dipper, one before the body of the bear/ body of the dipper begins with a magnitude of 1.77

- Dubhe “The Bear” is located in the top right corner of the body or bowl of the ladle of the Dipper with a magnitude of 1.79

- Alkaid “Leader of the Mourners” is located at the far end of the tail of the bear/ handle of the ladle with a magnitude of 1.86

- Mizar “Waist Cloth” is the second star in the handle of the ladle/ tail of the bear with a magnitude of 2.27. What we see as Mizar is actually a double-star containing Mizar and Alcor and was the first double star to ever be photographed as they can easily be separated with a decent pair of binoculars.

- Merak “The Loins” is at the bottom right corner of the ladle with a magnitude of 2.37

- Phad “Thigh of the Bear” is the bottom left corner of the ladle with a magnitude of 2.44

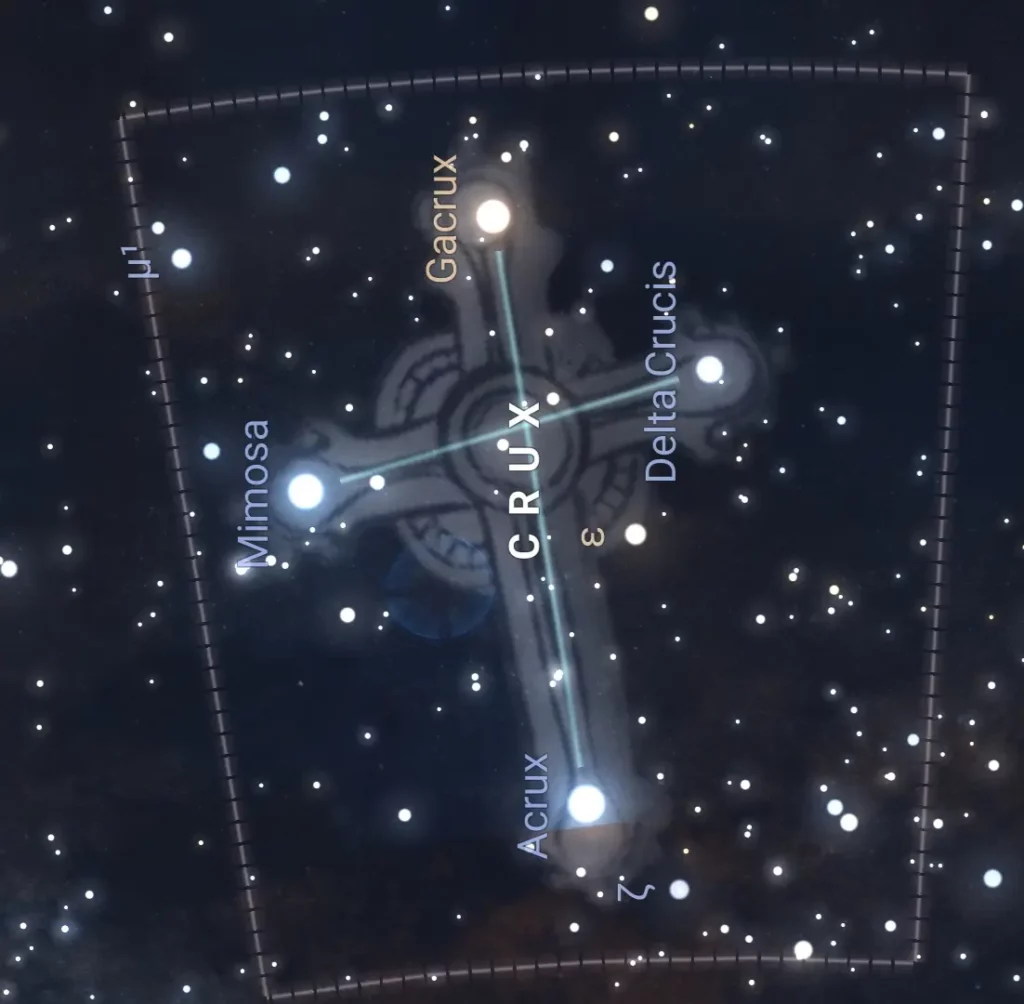

Crux (the Southern Cross)

One of the most familiar constellations in the southern hemisphere, Crux is an easy constellation to identify, due to its cross shape and bright stars. Since the southern hemisphere does not have a bright star near its pole, Crux was used to draw a line to determine the location of the south celestial pole, which is actually located in Octans. It is only visible from latitudes south of 27 degrees and completely below the horizon in most parts of the northern hemisphere.

Crux is the smallest constellation in the night sky with a total area of only 68 square degrees and is bordered by Centaurus on the east, north, and west, and Musca to the south. Ptolemy actually included it as part of Centaurus in his original 48 constellations because at that time it was still visible in the northern hemisphere due to the procession of the Earth’s axis and therefore astronomers noted when it disappeared. Many attributed this disappearance to the crucifixion of Christ and by the year 400, the stars were no longer visible from Europe. They became their own constellation in 1592.

The ancient Inca knew Crux as Chakana, “the stair” while the Mori called it Te Punga, “the anchor”, and the ancient aboriginal people of Australia, saw it as part of the head of the Emu in the Sky. Today, it is represented on the Australian flag and on the flag of Brazil.

There are 4 stars in Crux, making up the cross shape:

- Acrux “Alpha of Crux”, is the brightest and southernmost star of the cross, making it the bottom star from the North and the top star from the south with a magnitude of 0.77 (making it the 12th brightest star in the night sky).

- Mimosa “Actor” is to the east of Acrux with a magnitude of 1.25.

- Gacrux “Gamma of Crux” is across from Acrux with a magnitude of 1.63.

- Decrux “Delta of Crux” is across from Mimosa and has a magnitude of 2.79.

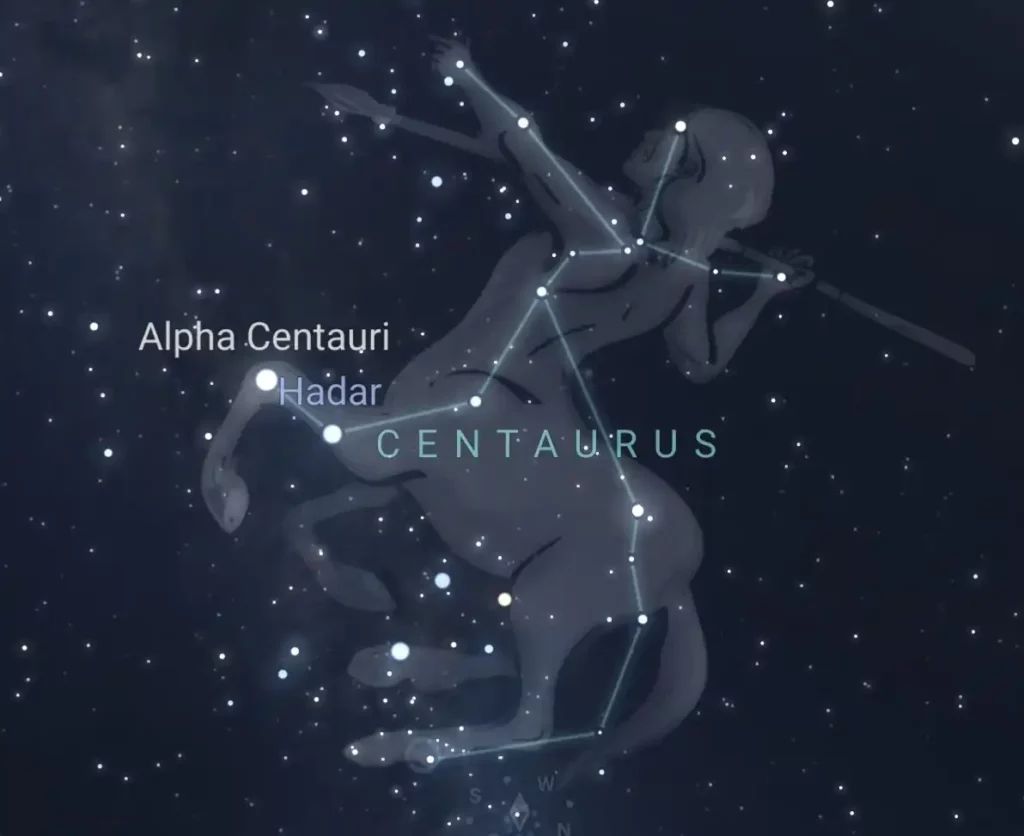

Centaurus (the Centaur)

This is a very old recognized collection of stars dating back to the ancient Babylonians who referred to it as the Bison-man, depicting it as a 4-legged bison with the head of a man. It is also one of the 48 original Ptolemy constellations, representing the half-man half-horse creature from Greek mythology and is often assumed to be Chiron who was accidentally wounded by Hercules and was posthumously honored by the half-god with a place in the stars.

Especially under a dark sky, you can see how this constellation is represented with a centaur as you can trace out the multiple legs with a body on top including a head and two arms.

Centaurus contains many bright stars:

- The brightest star is Rigel Kentaurus “Foot of the Centaur”, located in the bottom of the leg with a magnitude of -0.01. Rigel Kentaurus is also known as Alpha Centauri, the closest star to our solar system and the third brightest in our night sky.

- Directly to the right is Hadar “The Settled Land” with a magnitude of 0.61 making it the tenth brightest star in our night sky.

- Menkent “Shoulder of the Centaur” is high above Hadar, passing two decently bring stars and a handful of fainter ones at a magnitude of 2.06.

- Muhlifain “Two Things” is located at the other hip for the centaur’s other legs at an upward diagonal to the right Hadar with a magnitude of 2.20.

- Epsilon Centauri is located above Hadar, forming a triangle body with Mulifain and the star above it (Alnair).

Related Article: Meet The Centaurus – The Half-Man Half-Horse Constellation

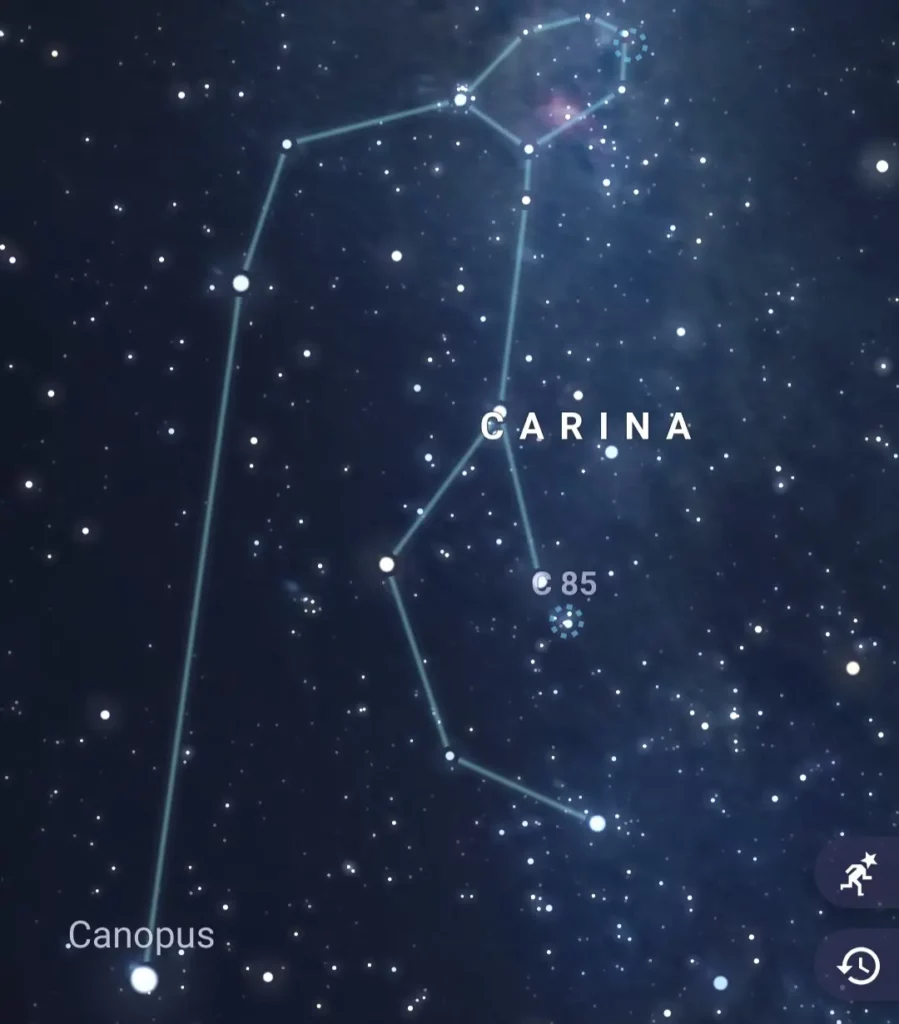

Carina (the Keel)

At 494 square degrees, Carina is a medium-sized constellation located in the southern hemisphere of the sky visible at latitudes south of 15 degrees and is completely below the horizon for latitudes north of 39 degrees. It is southeast of Canis Major and bordered by the constellations Centaurus, Chamaeleon, Musca, Pictor, Puppis, Vela, and Volans.

Carina was once part of the large constellation Argo Navis representing the ship of Jason and the Argonauts, which was one of the original 48 Ptolemy constellations. The constellation was later divided by French astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille into three smaller parts, including Carina the Keel, and added to the official list of modern constellations in the early 20th century.

Carina is made up of 11 stars that sweep around to the left and curl upwards slightly into a spiral:

- Canopus “Menelaus’s Helmsman” is the brightest star in the constellation (and second-brightest in the night sky) southeast of Canis Major with a magnitude of -0.74.

- The next brightest star is Miaplacidus meaning “Placid Waters” with a magnitude of 1.68at the bottom right of the spiral.

- The next brightest is Avior with a magnitude of 1.86 located above Miaplacidus and to the right, about halfway from Canopis down to where it begins to spiral back up.

- Aspidiske “Little Shield” is the next brightest with a magnitude of 2.21 located to the left of Avior and above Miaplacidus with two stars in between them.

Featured March Constellations

To make things a little simpler, constellations are grouped by hemisphere with the Northern ones first for each month, but be aware that many are visible from both hemispheres especially if you are closer to the equator.

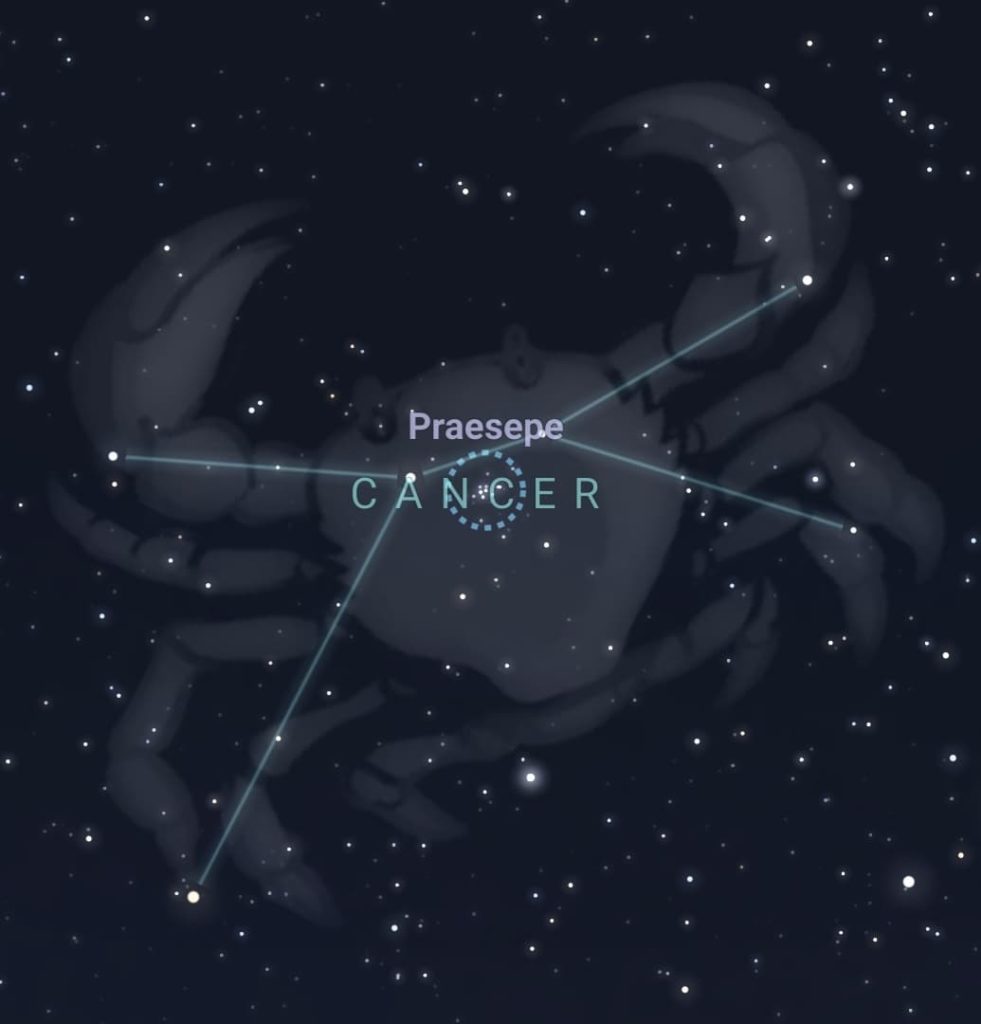

Cancer (the Crab)

Visible in the northern hemisphere at latitudes between 90 degrees and -60 degrees, Cancer is a medium-sized constellation of 506 square degrees, ranking 31st in size among the 88 constellations. The stars create an upside down Y with the left fork being almost half as short as the right. It is surrounded by Gemini to the west, Lynx to the north, Leo Minor to the northeast, Leo to the east, Hydra to the south, and Canis Minor to the southwest.

It is a fairly well-known constellation as it is part of the zodiac since it lies on the ecliptic or the path the Sun travels in the sky during the year. It was one of the original 48 constellations by Ptolemy. The constellation is of the crab in the story of the 12 labors of Hercules sent by Hera to distract him while he is fighting the Hydra. Depending on the version of the myth, Hercules either kicks it into the sky or crushes it under his foot. This constellation in other ancient cultures was believed to be the gate through which souls passed from Heaven to Earth when they were being born into mortal bodies.

It is a fairly dim constellation despite being well-known but some of its brightest stars include:

- Altarf, meaning “end or edge”, located as the furthest star on the right fork is the brightest with a magnitude of 3.54.

- Asellus Australis “Southern Donkey” is located at the fork

- Acubens “The Claws”, is located at the end of the left fork (it’s the only star on that side)

Asellus Borealis “Northern Donkey”, located directly above the Southern Donkey but slightly to the right.

Canis Minor (the Little Dog)

Visible in the northern hemisphere from December until April at latitudes between 90 degrees and -75 degrees, Canis Minor is a small constellation of only 183 square degrees bordered by Monoceros to the south, Gemini to the north, Cancer to the northeast, and Hydra to the east.

It was one of Ptolemy’s original 48 constellations depicting the smaller of Orion’s two hunting dogs, with its bigger and more well-known companion Canis Major, containing Sirius, the dog star, the brightest star in the sky. In another myth, it represents the Teumessian Fox which could not be outrun. Zeus turned both the fox and its hunter the dog Laelaps to stone and then placed them in the heavens as Canis Minor and Canis Major.

Canis Minor is the constellation with the least number of stars, only two: Procyon meaning “Before the Dog” as it rises in the night sky before Sirius and Gomeisa meaning “The Bleary Eyed”. Procyon is actually the 8th brightest star in the sky.

Lynx

At 545 square degrees, Lynx is a medium-sized constellation, ranking 28th. It is located in the northern hemisphere in and visible at latitudes between 90 degrees and -55 degrees, bordered by Ursa Major to the northeast and Cancer to the south.

Aiming to fill a large gap between the constellations Auriga and Ursa Major, Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius in the 17th century created the Lnx constellation because the stars were so dim one would have to have the eyes of a Lynx to see them.

The faint stars in Lynx create a dim, bumpy line north of Leo and Cancer:

- Alpha Lyncis is located at the bottom left of the constellation with a magnitude of 3.14.

- The next brightest star is 38 Lyncis with a magnitude of 3.82 located directly above and slightly to the right of Alpha Lyncis

The next brightest stars come in at a magnitude of 4.25. Alsciaukat “The Thorn” is located approximately in the middle with one dim star between it and 38 Lyncis and 2 Lyncis is the far right star in the constellation, located up and two the left from Castor in Gemini.

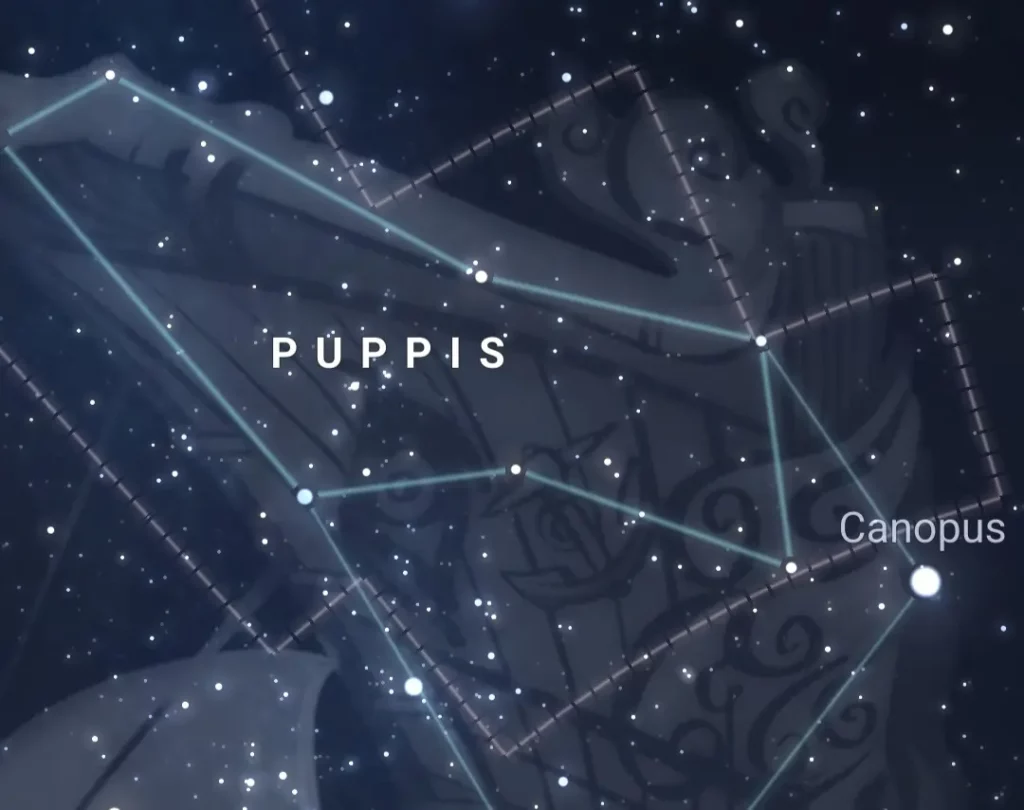

Puppis (the Stern) [Southern Hemisphere begins]

Puppis is the second constellation that used to be part of the larger constellation Argo Navis, the Stern (along with the previously mentioned Carina circumpolar constellation). Puppis resembles an upside down or mirror-image of a dipper. You could also see it as a horse or similar animal with a long neck with no legs.

Puppis lies southeast of Canis Major with its southernmost stars lying just north of Canopus in Carina. Some of the brightest stars, going in order from most bright to least include:

- Naos is the brightest star in Puppis with a magnitude of 2.25

- Tureis has a magnitude of 2.73

- Turais has a magnitude of 2.78

Tau Puppis is the last star in this constellation under 3 magnitude, barely at 2.95.

Vela (the Sails)

A mid-sized constellation of 500 square degrees, Vela ranks 32nd and is located in the southern hemisphere of the sky. It is completely visible at latitudes south of 30 degrees and bordered by Antlia and Pyxis to the north, Puppis to the northwest, Carina to the south and southwest, and Centaurus to the east. Be sure to look earlier in the evening to see Vela as it is wrapping up its time as a featured constellation.

Meaning “the sails” in Latin, it is the third constellation that used to be part of Argo Navis. Vela is an odd conglomeration of stars, creating a very bumpy, almost tank-like shape of stars with a relatively flat bottom, a semi-pointy top, and then stars that jut out on the left and right, creating harsh edges.

5 of the seven brightest stars are under three magnitude, making them fairly easy to see:

- Suhail al Muhlif “The Oath Taker” is located at the far right with a magnitude of 1.83

- Koo She “Bow and Arrows” is located below Suhail al Muhlif with a magnitude of 1.99

- Suhail “Smooth Plain” is located above Suhail al Muhlif with a magnitude of 2.21

- Markeb “Something to Ride” is located next to Koo She with a magnitude of 2.48

- Mu Velorum is located on the far side of the constellation with a magnitude of 2.69

Pyxis (the Compass)

A very dim, small constellation of 221 square degrees, ranking 65th in size, Pyxis is located in the southern hemisphere of the sky and is completely visible at latitudes south of 50 degrees. Again, you want to look earlier in the evening as its featured time is coming to an end. It lies near the three constellations that were once part of a larger group known as Argo Navis, the ship of Jason and the Argonauts.

The four main stars of Pyxis were once part of the ship’s mast and English astronomer John Herschel suggested renaming Pyxis as Malus, the Mast, but the new name was never accepted.

Pyxis is one of 14 southern constellations created by the French astronomer Abbé Nicolas Louis de Lacaille on his 1752 trip to the Cape of Good Hope. He named it la Boussole, which was later Latinized to Pixis Nautica, and eventually shortened to Pyxis. It represents a magnetic compass used by navigators, not to be confused with Circinus, which represents a draftsman’s drawing compass. Pyxis is essentially just a diagonal line of stars.

From Canis Major, find Puppis to the southeast and then continue to the east with a slight southward tilt for Pyxis. The brightest stars in this dim constellation are Alpha Pyxidis (magnitude of 3.68), Beta Pyxidis (magnitude of 3.95), and Gamma Pyxidis (magnitude of 4.03).

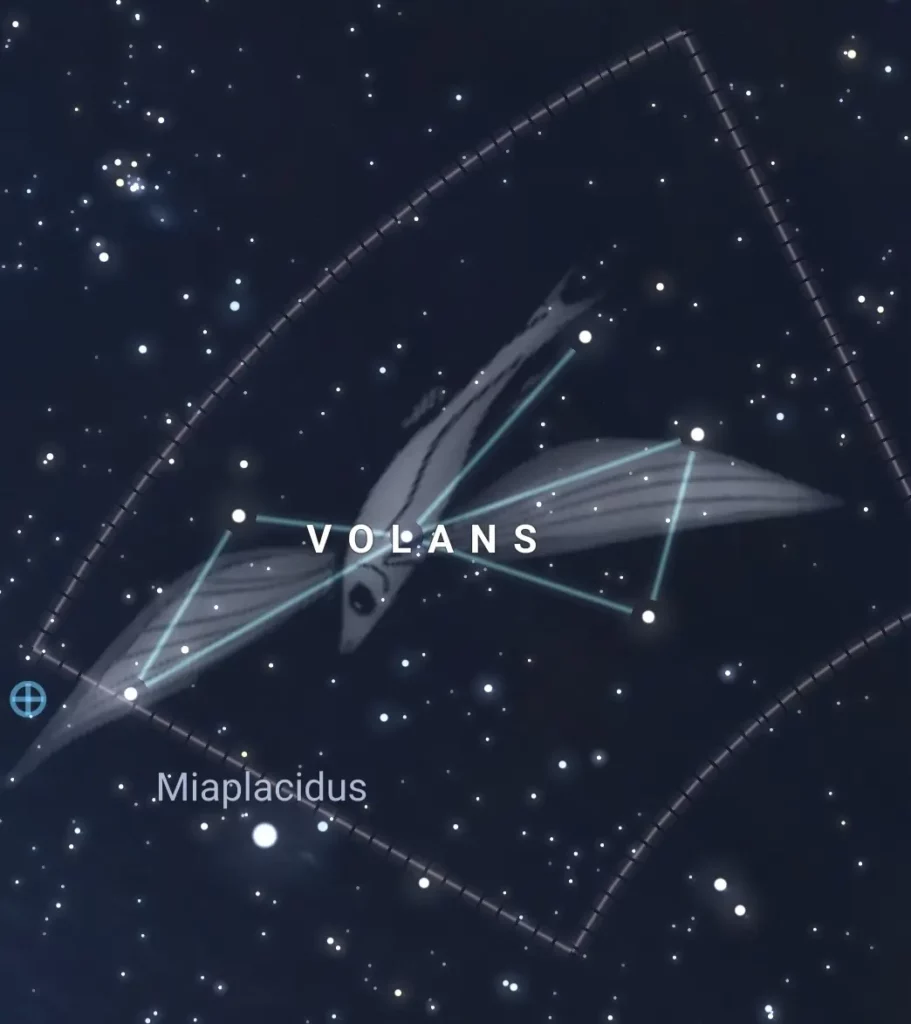

Volans (the Flying Fish)

This dim, small constellation of only 141 square degrees, ranking 76th in size, is located in the southern hemisphere of the sky. It is completely visible at latitudes south of 15 degrees from and is slowly heading under the horizon for the season so look in the early evening.

Originally named Vliegendenvis, it was one of 12 constellations named by the Dutch astronomer Petrus Plancius based on observations by Dutch navigators in 1598. It was later changed in 1603, to Piscis Volans, the flying fish, which was later shortened to Volans. The flying fish is a type of fish that can jump out of the water and glide through the air on special fins that resemble wings. Volans is often depicted as being chased by the dolphin fish in the constellation Dorado.

Volans is located southeast from Carina and technically is a circumpolar constellation, but is small and dim, making it hard to find.

Volans is shaped vaguely like a jumping fish or upside down whale with a line for a tail on the left and then the main body on the right. Again, these stars are very dim, but some of the brightest include Beta Volantis (3.77 magnitude), Gamma Volantis (3.78 magnitude), Zeta Volantis (magnitude of 3.93), and Delta Volantis (magnitude of 3.97).

Featured April Constellations

Leo (the Lion)

Leo is the the 12th largest constellation with an area of 947 square degrees. It is visible at latitudes between 90 degrees and -65 degrees, appearing in the north in the Spring. It is bordered by the constellations Cancer, Coma Berenices, Crater, Hydra, Leo Minor, Lynx, Sextans, Ursa Major and Virgo.

It is one of the zodiac constellations that lie on the ecliptic path that the Sun travels through and is fairly easy to spot with its coat hanger shape of various bright stars.

- The brightest in the constellation and 22nd brightest in the night sky is Regulus “Heart of the Lion” located at a diagonal from the tip of the hook of the coathanger south with a magnitude of 1.36. It was seen in ancient times as a guardian of the heavens.

- Algiebra “Forehead of the Lion” is the next brightest, located where the hook joins the body of the coathanger and above and to the left of Regulus with a magnitude of 2.08.

- Denebola “Tail of the Lion” is a blue-white subgiant star located at the tail of the lion or the far tip of the coathanger at a magnitude of 2.14.

- Zosma “Hip of the Lion” is a blue-white subgiant star located on a diagonal up from Denebola and on approximately the same line as Algiebra, forming the hip of the lion or filling the top edge of the body of the coathanger with a magnitude of 2.56.

- Ras Elased Australis “Head of the Lion” up and to the right from both Regulus and Algiebra forming a wonky triangle or Y shape (there is another star in between those two forming the center of this Y shape that is a little dimmer) with a magnitude of 2.98.

Leo Minor (the Lion Cub)

This small constellation with an area of 232 square degrees, ranking 64th, lies between Ursa Major to the north and Leo the the south and is completely visible at latitudes north of -48 degrees during the winter to spring season, but look int the early evenings now as it is slowly moving under the horizon.

These stars were originally considered to be part of Leo, but Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius first depicted Leo Minor as a separate constellation in 1687 as one of ten new constellations in his new star atlas, Firmamentum Sobiescianum. It is the only constellation with no alpha star designation due to an error when the constellation was cataloged.

Leo Minor looks like a backwards kite (shorter part of the kite at the back/ bottom) or a fish. All of the stars are faint, but a few of the brightest include 46 Leonis Minoris/ Praecipua “Principal Star”located at the far tip of the kite or head of the fish with a magnitude of 3.83, Beta Leonis Minoris located at the top point of the kite with a magnitude of 4.22, and 21 Leonis Minoris located at the point where the tail joins with the kite with a magnitude of 4.49.

Antlia (the air pump) [Southern Hemisphere begins]

Antlia is a small faint constellation with an area of 239 degrees and ranked 62nd, which occupies a mostly empty region of the sky and contains only faint stars. It is located in the southern hemisphere of the sky and can be seen at latitudes between 45 degrees and -90 degrees. Look for it in the early evening as it is slowly falling beneath the horizon.

Antlia is bordered by the constellations Centaurus, Hydra, Pyxis, and Vela as it lies in the space between the major, more visible Centaurus and Hydra with the ship constellations that formerly made up Argo Navis to the West.

It is another one of the 14 constellations named by French astronomer Abbé Nicolas Louis de Lacaille in the 18th century to fill in empty spaces in the southern hemisphere. Originally named “Antlia Pneumatica” to commemorate the invention of the air pump by French physicist Denis Papin and depicted as a single-cylinder vacuum pump used in Papin’s experiments, it was later depicted as a more advanced double-cylinder pump and was officially adopted as one of the 88 modern constellations in 1922.

The dim stars create a triangle with a line extending to the final star including: Alpha Antilae located at the far left point of the triangle with a magnitude of 4.28, Epsilon Antilae, located down and to the right of Alpha Antilae to create the bottom right point of the triangle with a magnitude of 4.51, Iota Antilae located down and to the left of Alpha Antilae with a magnitude of 4.60, and Theta Antilae completes the triangle above and between Alpha and Epsilon Antilae with a magnitude of 4.79.

Chamaeleon

As one of the smallest constellations in the night sky at only an area of 132 square degrees and ranking 79th, Chamaeleon is only visible below the equator as it is also a circumpolar constellation, south of Volans and southwest of Crux.

It is another of the twelve constellations created by the Dutch astronomer Petrus Plancius, first appearing on a celestial globe in 1597. It is often depicted as a chameleon sticking its tongue out to catch the fly represented by the neighboring constellation Musca.

The stars begin to form a rectangular shape on the left but then are stretched together to form a point with two stars at the far right end. They are all dim stars but rank as such, starting with the brightest:

- Alpha Chamaeleontis (magnitude of 4.06) located at the far right point.

- Gamma Chamaeleontis in the middle top of the constellation with a magnitude of 4.11

- Beta Chamaeleontis in the far left bottom corner with a magnitude of 4.25

- Theta Chamaeleontis directly beneath Alpha Chamaeleontis on the far right with a magnitude of 4.35

- Epsilon Chamaeleontis and Delta-1 Chamaelontis are the faintest of the constellation clocking in at magnitudes 4.88 and 5.47 respectively and are located in the far right top corner and lower middle respectively.

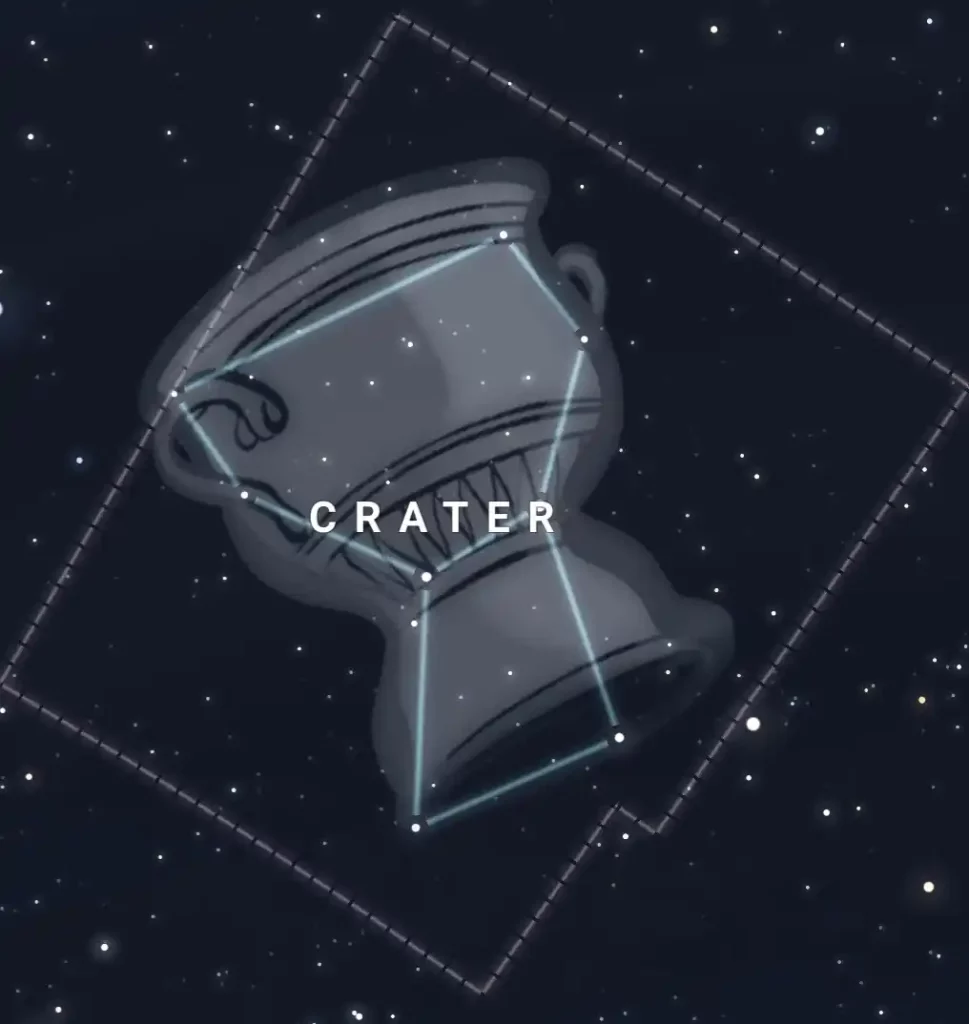

Crater (the Cup)

This dim, small constellation with an area of 282 square degrees, ranking 53rd, is located in the southern hemisphere of the sky and is best seen in the northern hemisphere in April, completely visible at latitudes between 65 degrees and -90 degrees. It is bordered by the constellations Hydra to the West, Corvus, and Virgo to the East, and Leo, Sextans to the North.

It is one of the original 48 constellations from Ptolemy and is usually depicted as a two-handed chalice. It represents the goblet of the Greek god Apollo and is associated with the story of Apollo and his sacred crow. Apollo sends the crow to fetch water with the cup, but it gets distracted by a fig tree and waits a few days for the figs to ripen. He finally brings the water-filled cup to Apollo along with a water snake as an excuse for being late, but Apollo sees through his lies and in a fit of anger casts all three, the cup, the crow, and the snake, into the sky to become the constellations Crater, Corvus, and Hydra.

The collection of stars does vaguely resemble a cup or a body with arms outstretched overhead. There are 8 stars with only 1 of them being brighter than magnitude 4. Labrum “The Tip”is the brightest, located at the point where the right side of the cup joins with base with a magnitude of only 3.56. After that, the next brightest include: Alkes “The Cup” (magnitude of 4.07), Gamma Crateris (magnitude of 4.08), Al Sharas “The Rib” (magnitude of 4.48), and Theta Crateris (magnitude of 4.68).

Hydra (the Sea Serpent)

Hydra is the largest constellation in the night sky, covering an area of 1,303 square degrees and a length of over 100 degrees. Its southern end borders Libra and Centaurus and its northern end borders Cancer. It is best seen from the southern hemisphere, but can be observed in the north between January and May. It is visible at latitudes between 54 degrees and -83 degrees.

It was one of the original 48 constellations listed by Ptolemy, and is an ancient constellation with roots in many different cultures. We already saw it in Greek mythology where it represents the water snake brought to the god Apollo by the crow, Corvus. It may also represent the hydra (a giant beast with the body of a dog and many snake-like heads that grow back with more after each one was cut off) from the myth of Hercules and his twelve labors. In Hindu mythology, it represented one of the Nakshatras of Hindu astrology, Ashlesha. The Chinese saw it as the Vermilion Bird and the Azure Dragon.

This constellation was once much larger, but was later split into Sextans, Crater, Corvus, and a slightly smaller Hydra.

Hydra has many stars, at least 16 notable ones under 4.5 magnitude, too many to list here. The brightest is Alphard “Heart of the Hydra”with a magnitude of 2, located toward the northern end of the constellation near Monocerous and Cancer. The next brightest is Gamma Hydrae with a magnitude of 2.99 located near the tail end on the eastern side, near Libra and Centaurus.

Hydrobius “Water Dweller” and Ashlesha “Serpent” are located in the cluster of stars at the head of the constellation on the north, with a magnitude of 3.11 and 3.38 respectively. Nu Hydrae and Pi Hydrae are located near the tail end with magnitudes of 3.12 and 3.25 respectively.

Sextans (the Sextant)

This dim, mid-sized constellation with an area of 314 square degrees, ranking 47th, is hard to find even under ideal conditions. It is best seen from the southern hemisphere from January through May and is located near the celestial equator, between Hydra and Leo.

It essentially looks like a wonky kite or a right triangle the was pinched and elongated, creating a peak instead of a right angle. Again, the stars are very dim and difficult to find, but the “brightest” is: Alpha Sextantis located at the top of the triangle or the right point of the wonky kite with a magnitude of 4.48, northeast of Alphard in Hydra. It is considered to be an equator star as it lies within a quarter of a degree from the celestial equator.

Some deep sky objects in and near Sextans include:

- NGC 3115/ the Spindle Galaxy: a lenticular galaxy nearly edge-on to our line of sight and is also the nearest galaxy believed to contain a supermassive black hole at its center.

- NGC 3169 and NGC 3166 are a pair of spiral galaxies that appear very close together and will eventually merge to form a single larger galaxy.

- Sextans A and Sextans B are both irregular galaxies and the latter is one of the smallest irregular galaxies known to contain planetary nebulas.

Featured May Constellations

Virgo (the Maiden)

It is well known as one of the zodiac constellations lying on the ecliptic and since the Sun passes through Virgo in mid-September, it announces the harvest in many cultures. It was one of Ptolemy’s original 48 constellations and is an ancient grouping of stars recognized by different cultures. The Babylonians knew it as “The Furrow”, representing the goddess Shala’s ear of grain.

To the Romans it represented by the goddess Ceres, the mother of Prosperina and her festival was in the second week of April,when the constellation appears in the spring skies. She was also sometimes identified as the virgin goddess Astraea, holding the scales of justice represented by the constellation Libra.

Virgo is usually depicted on charts as a maiden with angelic wings holding two ears of wheat, one of which is marked by the bright star Spica. The stars create a stick figure lying across the sky with her arms and legs as well as even stars in her head fairly visible including:

- Spica “Ear of Wheat” as the brightest star in Virgo and the 15th brightest star in the night sky with a magnitude of 0.98.

- Porrima “Goddess of Childbirth” is in the body/ torso of Virgo with a magnitude of 2.74.

- Vindemiatrix “Vine Harvestress” is in the opposite hand of Spica with a magnitude of 2.83.

- Heze forms the hip joint with a magnitude of 3.38.

Canes Venatici (the Hunting Dogs)

These stars were originally included in Ursa Major by Ptolemy and were first depicted with Bootes in 1533 and then as their own constellation in 1687, representing the hunting dogs, Asterion and Chara, of Boötes as he hunts for Ursa Major and Ursa Minor.

The stars are shaped like a wide V with the right side being slightly longer than the left. Cor Caroli “Heart of Charles” is the brightest star, located at the focal point or joint of the V with a magnitude of 2.90. Chara “Dear” creates the right side of the V with a magnitude of only 4.26 and La Superba “The Gorgeous” is a red variable star actually separate from the V, above and to the left of Chara, with a magnitude of 5.42. It is one of the reddest stars in the sky.

Coma Berenices (Berenice’s Hair)

Visible in the northern hemisphere in spring and summer at latitudes between 90 degrees and -70 degrees, Coma Berenices is a medium-sized constellation occupying 386 degrees, ranking 42nd.

It is located North of Virgo, South of Canes Venatici, and west of Bootes.

It was originally considered part of Leo by Ptolemy, representing the tuft at the end of the Lion’s tail, but in the 16th century, was separated the stars out into a new constellation and was named after Queen Berenice II, the wife of Ptolemy III of Egypt, whose beautiful long hair was given to Aphrodite as a gift. Aphrodite was so pleased by this gift that she placed it in the night sky. To this day the constellation is known as Berenice’s Hair.

The constellation is essentially just a right triangle of three faint stars:

- Beta Comae Berenices is the brightest at the triangle’s center with a magnitude of 4.26

- Diadem/ Berenice’s Crown is located beneath Beta Comae Berenices with a magnitude of 4.32

- Gamma Comae Berenices is located to the right of Beta Comae Berenices with a magnitude of 4.35

Corvus (the Crow) [Southern Hemisphere begins]

Old collection of stars known since the Babylonians who saw it as a raven, sacred to Adad, the god of rain and storm. To the Greeks (including Ptolemy), we’ve already seen how it is depicted with the cup and the water snake, leading Apollo to punish him by throwing him into the sky and making him eternally thirsty, which is why crows caw.

It forms the shape of a kite extremely stretched and distorted on one side and a short tail. The four brightest stars in this constellation form a square asterism known as the Sail, or Spica’s Spanker (a kind of sail), because two of the stars point the way to Spica, the brightest star in the constellation Virgo.

Gienah “Wing of the Crow” is the brightest in the top right corner of the rectangular shape with a magnitude of 2.59. Kraz comes in second on the left side, creating the great distortion in the kite, being at about the same line as the bottom of the kite with a magnitude of 2.65. Algorab “The Crow” is at the top with a magnitude of 2.96. Minkar “Nose of the Crow” is at the bottom, down from Gienah and to the right of Kraz with a magnitude of 3.02. Alchiba “Beak of the Crow” is at the tail of the kite with a magnitude of 4.03.

Musca (the Fly)

Musca is another southern circumpolar constellation located Northeast of the Chameleon, North of Crux, and Southwest of Centaurus. This faint, small constellation covering an area of only 138 square degrees, ranking it 77th in the night sky.

It is another of the 12 constellations created by the Dutch astronomer Petrus Plancius and was named for its shape, which resembles that of a housefly. Musca was first depicted in Johann Bayer’s star atlas in 1603. It was originally called De Vlieghe, which is Dutch for “the fly” but had many name changes over the years until we finally settled on Musca, the fly.

The brightest stars include Alpha Muscae with a magnitude of 2.69, Beta Muscae with a magnitude of 3.05, Delta Muscae with a magnitude of 3.61, Lambda Muscae with a magnitude 3.68, and Gamma Muscae with a magnitude of 3.84.

“Spring” Stargazing Tips

On any night, you will see older constellations (including the last of the previous season) in the early evening, followed by the season’s highlights in the main portion of the evening (look to the South in the Northern hemisphere and to the North in the Southern Hemisphere), and finally a glimpse at upcoming constellations in the early hours of the morning before sunrise, in the East.

Days are getting longer in the North and shorter in the South. Make sure to continually adjust your stargazing times according to sunset times. Remember that you need at least an hour after sunset for decent stargazing, though there may be a few points of interest before then. The later you can wait, the more you will see.

Be sure to keep a close eye on the weather. The weather is changing and likely not very predictable yet. Keep an eye on the temperatures throughout the night and keep extra blankets, jackets, etc. on hand just in case. Rain is also very common in these transitional seasons so make sure the forecast is in your favor as you need clear skies. Be aware that good stargazing sites may be muddy due to melting snow and/ or rain so rainboots/ galoshes/ wellies/ other weather-resistant footwear may be a good idea, sitting on the ground may be out of the question, and extra cleaning of equipment such as chairs and tripods may be in order.

As always, look for a location away from city lights and keep in mind where cities or other sources of light pollution might be from that vantage point. If there is a city to the south of your stargazing location, it will still impact your view of that region of the sky even if your location is clear, especially near the horizon.

Think through the logistics of set-up and take-down on site such as how far you have to walk from the car to where you want to set up. Make sure you have lighting options, preferably red-light options to not ruin your night vision.

Consider downloading and/ or printing star maps, images of Messier Objects and deep-sky objects, activities, etc. ahead of time. Having these available without having to worry about service will be a weight off your mind. In the following guide, I’ll mention many deep-sky objects found in or near constellations that will only be visible with a large telescope, but having images of those objects can greatly supplement your experience so that you can get a fuller picture of the night sky even though you don’t have the equipment to see it yourself.

If you have access to a telescope and know how to use it, bringing it along is always a good idea, but not necessary. Your naked eye will be able to see much of the night sky with no magnification, especially if you are in an area with low light pollution on a clear night. You can also use binoculars and binocular stargazing guides to magnify the moon, visible planets, Messier objects, or certain double stars.

For more information, check out our previous articles about the different types of constellations.

Conclusion

We hope you’ve enjoyed our Spring Constellation Guide and have been able to plan out your next stargazing adventure with it.

There are many amazing constellations up in the next few months with some truly spectacular Messier Objects and other deep-sky objects, allowing you to experience different aspects of the universe while star-hopping through the night sky, no matter what side of the globe you are on.

So, as the season transition, we hope you are able to schedule some time to observe the night sky in all its glory.

Sarah Hoffschwelle is a freelance writer who covers a combination of topics including astronomy, general science and STEM, self-development, art, and societal commentary. In the past, Sarah worked in educational nonprofits providing free-choice learning experiences for audiences ages 2-99. As a lifelong space nerd, she loves sharing the universe with others through her words. She currently writes on Medium at https://medium.com/@sarah-marie and authors self-help and children’s books.

Wow! There's more to read 🚀

This constellation-related story is part of our collection of stargazing articles. If this piece sparked your interest, you’re sure to enjoy the fascinating insights offered in our subsequent articles.

Planetary opposition constitutes the best time to observe the planets with your telescope or binoculars.