Astronomers stunned by unprecedented short and hot flares emitted by a supermassive black hole

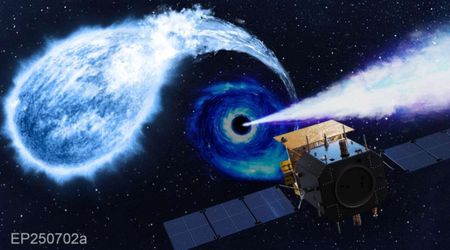

When a star drifts too close to a supermassive black hole, the latter tears it apart rather violently, creating a temporary disk of glowing gas that makes the otherwise imperceptible black hole visible. Such events are referred to as tidal disruption events (TDEs). One such TDE, designated eRASST J2344, has been exhibiting a complex pattern of X-ray eruptions. With Einstein Probe and XMM-Newton observations, a team of astronomers has discovered that the flares recur every 12 hours and last around 2 hours. What's interesting is that these flares are interspersed with unprecedentedly shorter, hotter flares. The study, published in Astronomy & Astrophysics, challenges the existing theories of how matter behaves when it comes very close to a supermassive black hole.

The bigger flares themselves, dubbed as quasi-periodic eruptions (QPE), occur only in a handful of cosmic sources and still remain a mystery. “Quasi-periodic eruptions are extremely rare, so I was already excited when I saw the Einstein Probe light curve,” said lead researcher Pietro Baldini, a PhD student at the Max Planck Institute of Extraterrestrial Physics in Germany, in a statement released by the institute. “But when the XMM-Newton data came in, my jaw dropped: not only had we discovered a new QPE source, but its behavior was completely unprecedented.”

The main X-ray eruptions follow a typical pattern for known QPEs. But the shorter and hotter flares, each of which lasts between 5 and 30 minutes, had not been observed in such systems before. As far as QPEs are concerned, they are believed to be a result of an orbiting star's periodic interactions with the accretion disk of a supermassive black hole. But while this can explain the main flares, the shorter, hotter flares still remain a mystery. They indicate that the matter near black holes is so complex that its behavior cannot be explained using the existing models. To get deeper insights into what is actually going on in J2344, the team has been granted additional observation time to further monitor the celestial event. This may help them figure out how the two types of flares are connected.

The discovery also highlights the growing power of modern X-ray astronomy. The Einstein Probe, armed with its wide-field optics and sensitive X-ray telescope, is an observatory uniquely capable of monitoring rare and interesting events like QPEs. “Since launch, Einstein Probe has opened an entirely new discovery space in X-ray astronomy,” said co-author Arne Rau at the Max Planck Institute of Extraterrestrial Physics in Germany in the statement. “This result is just a first glimpse of the kind of rare and unexpected phenomena we expect to find, and we are very excited about what comes next.” Indeed, astronomers like Rau hope to uncover more about supermassive holes and their extreme environments as the Einstein Probe continues to survey the skies.

More on Starlust

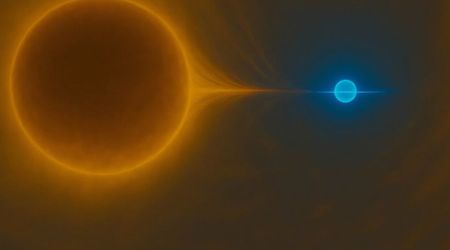

Scientists may have directly observed a black hole tearing apart a white dwarf for the first time