Hubble captures active black hole devouring spiral galaxy 250 million light-years away

The Hubble Space Telescope has captured a stunning cosmic event 250 million light-years away, revealing a supermassive black hole aggressively consuming material within the spiral galaxy UGC 11397. This galaxy, located in the constellation Lyra, initially appears to be a typical spiral with graceful arms of stars and dust, according to NASA.

A cosmic weigh-in 💪

— Hubble (@NASAHubble) June 27, 2025

Hubble observations, like the ones captured for this new #HubbleFriday view of UGC 11397, will help scientists weigh nearby supermassive black holes, and understand how black holes grew early in the universe’s history: https://t.co/XsIVK0rleK pic.twitter.com/CViZO3udoy

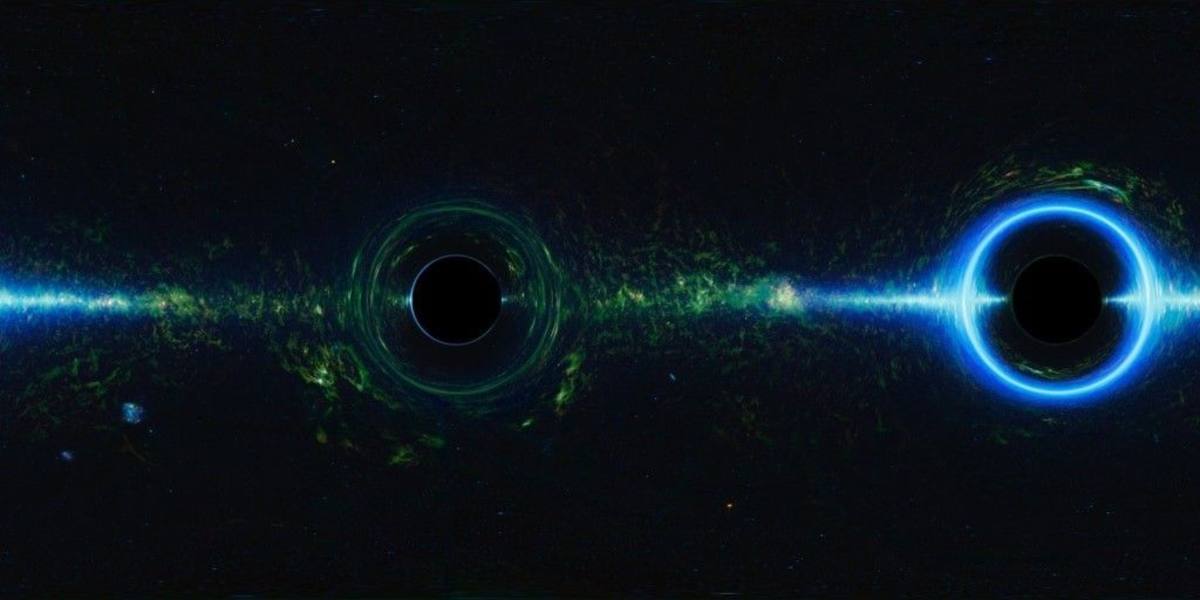

However, its core harbors a colossal secret: a black hole with a mass 174 million times that of our Sun, actively growing by ensnaring gas, dust, and even entire stars. This doomed matter heats up dramatically, producing a brilliant cosmic light show across the electromagnetic spectrum, from gamma rays to radio waves, with its brightness fluctuating unpredictably.

Despite thick dust clouds obscuring much of this activity in visible light, the black hole's vigorous feeding was confirmed through its powerful X-ray emissions. These high-energy rays can penetrate the surrounding dust, leading astronomers to classify UGC 11397 as a Type 2 Seyfert galaxy. This designation refers to active galaxies whose central regions, despite their intense activity, are hidden from optimal view by a donut-shaped cloud of dust and gas. Researchers are now leveraging Hubble to study hundreds of similar galaxies like UGC 11397, which host accreting supermassive black holes. These observations are crucial for precisely measuring the mass of nearby supermassive black holes, understanding their growth in the early universe, and even investigating how stars form in the extreme environments found at the very heart of a galaxy.

Astronomers broadly categorize black holes into three main types based on their mass: stellar-mass, supermassive, and intermediate, though the exact boundaries are subject to ongoing scientific refinement. There's also theoretical speculation about a fourth type, primordial black holes, which may have formed during the universe's infancy and remain undiscovered. Stellar-mass black holes form when massive stars, over eight times the Sun's mass, collapse after a supernova, typically resulting in a few to hundreds of solar masses. They grow by absorbing surrounding matter and colliding with other objects. Many are found in X-ray binaries, where they pull gas from a companion star, creating X-ray emissions. Though only about 50 are confirmed in the Milky Way, estimates suggest there could be 100 million, as mentioned on NASA.

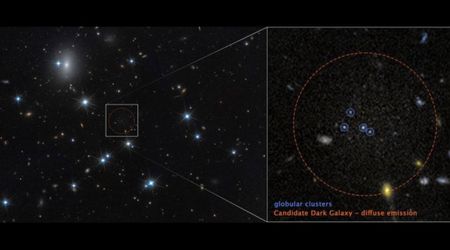

Conversely, supermassive blackholes reside at the heart of most galaxies, including our own Sagittarius A*, a pronounced eye star, which is 4 million times the mass of the Sun. These behemoths range from hundreds of thousands to billions of times the Sun's mass. Their origins are still a mystery, though some may have formed from the collapse of early supermassive stars. They grow by consuming smaller objects and merging during galactic collisions. The existence of intermediate-mass black holes, bridging the gap between stellar and supermassive types (hundreds to hundreds of thousands of solar masses), remains a puzzle. These "missing links" are theorized to form from stellar-mass black hole collisions, but are hard to confirm. Lastly, primordial black holes are hypothetical, believed to have formed during the first second after the birth of the universe. While unproven, more massive primordial black holes might still exist, while smaller ones may have evaporated over cosmic time.

Further extending its reach, the NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope continues to offer unavailable insights into the dynamic processes shaping galaxies, Recent observations highlight both vigorous star formation and more subdued environments in our cosmic neighborhood, exemplified by the dwarf galaxy NGC 4449 in the constellation Canes Venatici, which stands out as a "starburst galaxy"

Pretty in pink 🎀

— Hubble (@NASAHubble) June 20, 2025

Despite its relatively small size, the dwarf galaxy NGC 4449 forms stars at a much faster rate than expected. The bright pink patches throughout show star-forming regions!

Find out more on this #HubbleFriday view: https://t.co/J4SGeMK9Te pic.twitter.com/ImhxHLPCjs